I have created blog re-examining Thornton's work as as architect. Here is link to the table of contents of the blog which is organized as a seventeen chapter book:

https://ingeniousa.blogspot.com/2023/01/table-of-contents-case-of-ingenious-a.html

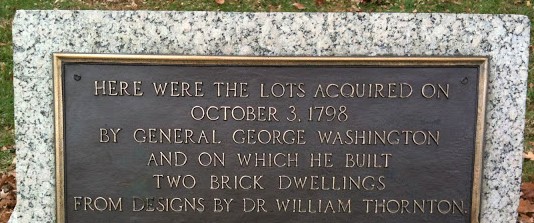

A Plaque Marks the Spot of the Capitol Hill Houses

In 1799 work began on John Tayloe's Octagon house, Thomas Law's five story house southeast of the Capitol and George Washington's two houses just north of the Capitol. Thornton is credited for designing all three with his design for the Octagon almost as famous as his design for the Capitol. Actually, he did not design any of those houses.

Most source credit Thornton for designing Washington's houses based on architect Glenn Brown's confident assertion in 1896 that "Dr. Thornton was the architect and superintendent, as shown by letters of Washington," but Brown neither quoted nor cited any letters. Future historians found no reason to disagree. Over a century of unexamined repetition led Ron Chernow, George Washington's 2010 biographer, to credit Thornton as the houses' designer.(1)

In 1905, a biography of the English Quaker poet Thomas Wilkinson quoted a letter Thornton wrote to his old friend in 1799:

The late President General Washington, who appointed me here, continues to honor me with his particular friendship. I frequently visit and am visited by this great and good man, besides corresponding. He is now building two Government Houses in this city, and has confided to me his money transactions here, as a friend... My public engagements continue as a commissioner. We enjoy uninterrupted health in this place. It is one of the finest situations in the world. I am under obligation to thee for thy beautiful and philanthropic poem on "War." It does thee much honor and I peruse it with pleasure. (2)

The biography was written by Wilkinson's great-niece and gained no currency in America. It seems unlikely that if Thornton had written that he designed the houses, that she would have cut that out of the letter.

In 1800, Thornton's wife began keeping a diary. In the wake of Washington's death on December 14, 1799, his executors needed information on the almost finished houses. In her January 3 entry, Mrs. Thornton wrote that a letter from Mount Vernon requested "information respecting the General's two houses building near the Capitol the money paid to the undertaker of them having all gone thro' my husband's hand, he having Superintended them as a friend."(3) She did not mention that he designed the houses in that entry or anywhere else in her diary.

The correspondence between Washington and Thornton makes clear that Thornton did not design Washington's houses. The historians at the Mount Vernon Museum pride themselves in celebrating Washington's life through his correspondence. They refrain from crediting Thornton for designing the houses and instead suggest he collaborated in perfecting the design. They note that Washington sent a sketch of the houses design to Alexander White who was then one of three federal commissioners preparing the new capital for the reception of congress in 1800. They note that Washington "requested that his plan be examined by a second commissioner, Dr. William Thornton."(4)

Actually, the letter doesn't quite say that. Washington sent a

sketch of the floor plan for "plain" houses that White

could use to enter into a contract with a builder. He seemed quite

proud of his sketch: "I enclose a sketch,

to convey my ideas of the size of the houses, rooms, & manner of

building them; to enable you to enter into the Contract. This sketch

exhibits a view of the ground floor; the second, & third, if the

Walls should be run up three (flush) stories, will be the same; and

the Cellars may have a partition in them at the Chimnies—"

Then Washington added: "My plan when it comes to be examined, may be radically wrong; if so, I persuade myself that Doctr Thornton (who understands these matters well) will have the goodness to suggest alterations."(5)

That certainly isn't a request for his plan to be examined by Thornton. However, there are no more letters extant between Washington and White about the houses. There is an interesting file of letters about the houses between Washington and Thornton. The contract between Washington and the builder George Blagden is also in Thornton's handwriting. In addition, there is evidence in other letters that Washington saw a "plan of Doct. Thornton's" two weeks before he sent his plan to White.

Such evidence can be construed as proof that the General must have bowed to the architect when designing his houses. But on close examination, that evidence doesn't hold up.

On August 27, 1798, Washington sent Thomas Peter a brief letter about a monetary transaction, and then added: "Doctr Thorntons plan is returned with thanks; our love to Patsy." Peter had visited Mount Vernon the day before, and Patsy was Martha Washington's grand daughter and Peter's wife. Two days later, Peter acknowledge his receipt of "Doctr Thorntons Plan."

For an explanation of that plan, the editors of Washington's papers refer readers to "Peter to GW, 18 Oct. 1798, in Harris, Thornton Papers 1:473–74." Actually the letter in question is GW to Thornton and in it Washington doesn't discuss the design of the houses, but it is the first letter he wrote to Thornton in which he mentioned the houses. In their commentary on the letter, the editors of Thornton's papers note that Washington first mentioned the houses in a September 12 letter to Alexander White, and note that Washington "had reviewed a plan that WT apparently prepared for Thomas Peter...." They refer the reader to Washington's August letter to Peter.

By associating Washington' October letter discussing his houses with two August letters mentioning "Doctr. Thorntons plan," the editors imply that the plan Peter shared with Washington informed the design of his houses. Ergo,the ideas of Thornton informed the design of the houses.(6)

However, "Dr. Thorntons plan" likely had nothing to do with house design. The first documentary evidence that Thornton made a plan for Thomas Peter is May 1808 when Thornton's wife noted that her husband "drew a plan for Peter."(7) Historians believe that was one of his many designs for Tudor Place, the Peter's mansion in Georgetown completed in 1815.

In 1798, Peter, Washington and Thornton had something in common that explains why they would all be interested in a plan made by Thornton. They all owned lots around the public reservation slated to be the site of the National University which was a dream Washington had cherished for years. He had also donated his Potomac Company stock to help fund it. Stock in a company that would charge tolls at the locks around the falls of Potomac had to one day be very valuable.

Thornton owned two lots in

Square 33 and a large wooden house there that he rented out.

Washington owned lots in Square 21, and the Peter family owned the houses in

Square 22, as well as many of the lots in the area that they retained

by virtue of owning the land in 1791.(8)

In January 1796, Washington asked the commissioners if anyone was working on a "plan" for the National University. Thornton told his colleague Alexander White that he was working on a "plan" for the university and soon wanted to pass it around to friends for comment. Since at that time the site of the university was up in the air, Thornton was likely referring to the curriculum and organization of the university. In the fall of 1796, Thornton persuaded the president to place the university on Peter's Hill. The draft of his letter to president begins "the wish you have so frequently expressed of seeing an university founded at the seat of government upon the most extended plan...." His draft of a memorial to be sent by the commissioners to congresses urges authorization for "promoting a plan" for the University. Congress briefly debated a memorial but did nothing.(9)

Thormton's plan in 1798 was likely a map showing the sites of the school's buildings on Peter's Hill which judging by the draft of the letter he sent to the president would include "the national library, museum menage, school for the mechanic arts, and many other appendages to the university..." In a December 26, 1800, diary entry, Mrs. Thornton wrote, "Mr. Blodget making a sketch of Dr. T's plan for our University on Peter's Hill."(10) In 1798, with Thornton's plan in hand, Washington and the Peter family would know how their lots related to the library, museum and schools of various arts.

Washington's reference to Thornton in his September 12 letter to White can be taken as an appreciation of Thornton's genius but not when it was written to White and not when it was written about "plain" houses. Washington wanted to rent his houses to a hotel keeper who would board congressmen when congress convened in the city in December 1800.

George

Washington's

houses, source: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/george-washingtons-townhouse-lots

When rubble was needed during construction of the New Capitol much of the ground in front of the buildings were removed. A new bottom story was added to get the houses closer to the street. Today, the whole hill is a street level slope toward Union Station and the houses are long gone with only a plaque like a gravestone marking the spot. Its inscription credits Thornton for designing the houses. Thornton did not build the third house.

White was a Virginia lawyer and former congressmen who Washington made a commissioner to keep a check on Thornton who in his first six months as a commissioner seemed more interested in thwarting investment in the city and lobbying for a Capitol even grander than the one he designed. He wanted to undo changes made to his design, and his arguments relied heavily on British books on architecture., especially Colen Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus and William Chambers' Treatise on Civil Architecture. At least in his own mind, Thornton established himself as the resident expert.

For

example, in January 1798, Thornton chided his colleagues for not having a rose on top of a pilaster recut so that it would be 1 and 3/4 inch larger, Thornton wailed that the mistake "will

remain, forever, a laughing stock to architects." It was "not in the proportion recommended by Sir Wm. Chambers

in his work on architecture...." Then White went to Philadelphia and

while there, he

tried to procure mahogany for the doors of the Capitol. A deal fell

through and rather than possibly delay progress on the building, he

and Commissioner Gustavus Scott voted to have pine doors with a mahogany

finish. Thornton dissented. It was his shortest dissent but included

his usual refrain. They must do what was "recommended by the

best writers in architecture...."(11)

After getting the September 12 letter from Washington, White asked his colleagues for advice on two favors Washington asked for in the letter. He wanted commissioners to get title to the two lots he wanted on Capitol Hill and to make a contract with a reputable builder. That likely was when Thornton first learned of the project.(12).

There is no evidence that Thornton offered written advice on the design. On September 21, along with his colleagues, he was with the president as he chose his lots. But there is no evidence that he talked about the design. That same day he wrote to his colleagues asking them to give him the other part of his prize for designing the Capitol. Along with $500, he had won but did not claim a building lot in the city. He then began to arrange that the prize lot was one of the two lots next to lot the president's lots. He did not inform the president about the arrangement until October 25.(13)

Thornton took pains to involve himself in the project, but not to change Washington's design. In that October letter he offered to build a house next to Washington's and bear the full expense of the party wall after getting specifications for the wall from Washington's builder. That said, he allowed that he did not yet have the money to start building. Washington's graciously welcomed the party wall and didn't want Thornton to pay for it all. He never built on the lot.

Meanwhile, through October negotiations continued with the builder. As Thornton put it in a letter to the president, he and White "formed" a contract that specified dimensions and building materials. The final copy of the contract was written in Thornton's handwriting which suggests he, more than White, drew up the contract. However, a letter Washington wrote to commissioners on November 5 describes a contract hammered out by himself and the builder, who came to Mount Vernon on October **. Thornton wasn't there. In a letter to the commissioners, Washington wrote: "The agreements are drawn on unstamped paper; but I presume it may be stamped in George Town. If it cannot be done there, Doctr Thornton will be so good as to have new agreements drawn for me on stamped paper." Although the final document was only in Thornton's hand because he was also a county magistrate who could make documents official, the editors of Thornton's paper suggest that in drawing the contract, Thornton made design decisions that "extended to such details as the selection of molding."

In his October 18, before the contract was finalized, Washington told Thornton that he hoped to save money by having his slaves do some of the carpentry. He asked Thornton to get Blagden to particularize exactly what he needed. by way of planks and scantling. Plus, "it would be expected of him too, to give the moldings and dimensions of such parts of the work as would be prepared by my own people at this place."

Thornton replied that after asking Blagden for the dimensions, "I meant to obtain a specimen of different moldings, thinking your people could work better by them, than by drawings." That hardly seems to be a design decision and nothing came of it since once he met with Blagden, Washington decided not to use his slaves.(14)

Once the contract was signed Washington would be obliged to send money to the builder to buy building materials. He had sent his money for the two lots to the commissioners even though one lot was privately owned. Realizing it may seem unseemly to have the commissioners pay his builder, he asked Thornton to privately do that for him. In his October 28 letter, he wrote: “as you

reside in the City, and [are] always there, and have moreover been so

obliging as to offer to receive the Bills and pay their amount (when

presented by Mr Blagden) I will avail myself of this kindness.”

Of course, Thornton agreed. By doing so, he guaranteed an on-going correspondence with George Washington until the house was finished.(15)

Questions about the design did come up in their correspondence. For example, in a December 21, 1798 letter, Thornton advised Washington to put a parapet on the roof of his houses. Characteristically, he noted that the City of London made it a rule that houses have parapets. Washington didn't take that advice. A clash of quotes all but proves that Washington's assuring White that Thornton would correct errors was a joke between the two men which alluded to the inevitability of Thornton finding fault.

Washington wrote: "I saw a building in Philadelphia of about the same front and elevation that are to be given to my two houses, which pleased me. It consisted also of two houses united - doors in the center - a pediment in the roof and dormer window on each side of it in front - skylights in the rear. If it is not incongruous with rules of architecture, I should be glad to have my two houses executed in this style."

Thornton wrote back: "it is a desideratum in architecture to hide as much as possible the roof - for which reason in London, there is a generally a parapet to hide the dormer windows. The pediment may with propriety be introduced, but I have some doubts with respect to its adding any beauty."

Washington replied: "Rule of architecture are calculated, I presume, to give symmetry, and just proportion to all the orders, and parts of the building, in order to please the eye. Small departures from strict rules are discoverable only by skilful architects, or by the eye of criticism, while ninety-nine in a hundred - deficient of their knowledge - might be pleased with things not quite orthodox. This, more than probable, would be the case relative to a pediment in the roof over the doors of my houses in the city.(16)

That was the second time Thornton used his experiences in London to try to instruct the General. In late October Thornton suggested that despite local building regulations, the houses destined to entertain boarders be set back just as they were in London to accommodate large casks and make a subterranean kitchen more airy. Washington agreed but declined asking the board to change a regulation he had proclaimed and Thornton enforced. (17)

Thornton was involved in a design change but only as a conduit of information between Washington and the builder.

In his response to a letter Thornton sent that has not been found, Washington wrote: "Your favor of the 28th instant, enclosing Deeds for my Lots in the Federal City—and Messrs Blagden & Lenthals estimate and drawing of the Windows—dressed in the manner proposed—came to my hands yesterday. The drawing sent, gives a much handsomer appearance to the Windows than the original design did; and I am more disposed to encounter the difference of expence, than to lessen the exterior show of the building—& therefore consent to the proposed alteration."1 Thanks to the way the letter was written, it is not clear who proposed the change in the design. It may well have been Thornton. However, either Blagden or his partner Lenthals, who was a carpenter, made the drawing. There are no more discussions of the design of the houses that Thornton never claimed credit for designing.(18)

Historians who don't credit Thornton for designing the houses credit him for superintending or overseeing their construction. That implies that after reviewing the design and contract, Thornton could rely on his understanding of building techniques and the cost of building materials to prevent cost over runs and delays. Thornton seemed as clueless as his colleagues

Washington bristled at Blagden's $12,982.29 estimate of the cost of the houses. He knew that Thomas Law had contracted to build a house, "not much if any less than my two," for under $6,000. Washington said he had calculated it would cost $8,000, or $10,000 at most. Washington decided "to suspend any final decision until I see Mr Blagdens estimate in detail, with your observations thereupon; and what part of the work I can execute with my own Tradesmen, thereby reducing the advances."

In the commissioners' reply, signed by Thornton, they assured him of Blagden's integrity, allowed that they were unable to say if the estimate was reasonable and regretted that the only man in their employ who could was at the time "confined by indisposition." That was James Hoban, architect of the White House, who, unlike Thornton, was a real architect.(19).

Rather than the novice Washington taking advice from the man who a century later would be proclaimed the greatest American architect of the 18th century, Washington schooled Thornton in building techniques. He reminded him to get window sashes painted before installation, instructed him on the proper mixture of sand in the paint for the walls and lectured him on plaister of Paris. After that lesson, Thornton referred Washington to a pamphlet on the subject written by a Pennsylvania judge. While president, Washington had asked the judge to do the research and write the pamphlet.(20)

However, there was a contemporary who credited Thornton for superintending the houses. In her diary, Mrs. Thornton noted apropos the houses that "the money paid to the undertaker of them having all gone thro' my husband's hand, he having Superintended them as a friend." And as a friend,Washington did not hold Thornton responsible for when the work began and how it progressed. A real superintending architect never got off that easily.

After signing the contract, Washington naively expected the contractors to make preparations for building. Washington was shocked to learn in March 1799, that nothing had been done to prepare the site or have building materials delivered. That would have been the responsibility of the superintending architect, if he had one. He didn't blame Thornton,(21)

Work on the houses began in the second week of April. In an April 19 letter, Thornton described what Blagden had done thus far. He also briefly acted like a supervising architect: "I visited the workmen the Day before yesterday, & they progress to my Satisfaction. I took the liberty of directing Stone Sills to be laid, instead of wooden ones, to the outer Doors of the Basement, as wood decays very soon, when so much exposed to the damp; but I desired Mr Blagdin would do them with as little expense as possible." Washington thanked him for the stone cills but ignored the lecture on the wood getting damp: responded that (Judging by the remaining letters he wrote to Washington, he never advised Blagden again.)(22)

Then in his April 19 letter, Thornton turned to the gossip of the day, He briefly reported the death of a mutual friends daughter as well as this item: "Mr J. Tayloe of Virga has contracted to build a House in the City near the President’s Square of $13,000 value."

While keeping Washington updated on his houses, Thornton never again mentioned the other house he supposedly designed and that was then being built. Of course, letters only provide a narrow window on what passes between people who might spend hours together in conversation. But letters we have to and about Thornton make clear that he had little interest in talking about private building. A letter from Washington's secretary to Thornton reveals the topics talked about when Thornton was at Mount Vernon. On September 12, 1799, Lear wrote to Thornton thanking him for some recent medical advice and continued

I am very happy to learn that the prospects in the city are brightening fast. You will become every day more and more important, and I have not a doubt but the improvements will be rapid beyond example. I hope the grand and magnificent will be combined with the useful in all the new public undertakings. We are not working for our selves or our children; but for ages to come, and the works should be admired as well as used. Your wharves and the introduction of running water are among the first objects. Let no little mindedness or contracted views of private interest prevent their being accomplished upon the most extensive and beautiful plan that the nature of things will admit of - and - But hold, I am talking to one who has considered and understands these subjects much better than myself...(23)

Thornton gloried in his role as the protector of the public interest and planner of public grounds. In May, Thomas Boyleston Adams, the First Family's third son, toured the city. In a June 9, 1799, letter to his mother, he described as "a democratic, philanthropic, universal benevolence kind of a man—a mere child in politics, and having for exclusive merit a pretty taste in drawing—He makes all the plans of all the public buildings, consisting of two, and a third going up. There was no mention of three notable private house then under construction: Washington's, Law's and Tayloe's.(24)

Thornton did defend the private interests of his great patron, as he saw fit. Once word got out that Washington was building, John Francis, who boarded congressmen in Philadelphia, expressed an interest in renting Washington's houses. Washington asked Thornton what the customary rent would be. Instead, Thornton turned Francis away. Since Francis also wanted to build back buildings behind Washington's houses, Thornton wrote to Washington that he “refused to name any price,” and Francis lost interest. But not to worry, if Francis hesitated to rent Washington's houses, Thornton had a better idea. He advised Washington to become a real estate developer, starting with the houses he was building:

...preserve them unrented, and keep them for sale, fixing a price on them together or separately; and I have no Doubt you could sell them for nine or ten thousand Dollars each, and if you were inclined to lay out the proceeds again in building other Houses this might be repeated to your Advantage, without any trouble, with perfect safety from risk, and to the great improvement of the City. I am induced to think the Houses would sell very well, because their Situation is uncommonly fine, and the Exterior of the Houses is calculated to attract notice. Many Gentlemen of Fortune will visit the City and be suddenly inclined to fix here. They will find your Houses perfectly suitable, being not only commodious but elegant.(25)

Washington didn't react to Thornton's suggestion. But the General almost plunged. Washington saw a lot that struck his fancy. Carroll owned it and Thornton inquired about its price. One benefit of Washington's building on Capitol Hill had been that it increased the value of all lots in the vicinity. Carroll could not lower his price just for him and assume other buyers would understand and gladly pay more. Washington lost interest and gave an excuse reserved for all gentlemen: he had expected that closing another deal would give him the means to proceed, but that deal fell through.(26)

Throughout the back and forth, there is no evidence that Thornton offered to design a house, not even one for the lot he owned next to Washington's. A New England gentleman bought the lot on the other side of Washington's houses. In an August 1 letter, Thornton told Law that he called on him "to recommend houses like the Generals,... but I think he has not yet determined what to do."(27)

In one letter he sent to Washington that summer, Thornton did mention seeing Tayloe. The first clearly documented meeting between Thornton and Tayloe took place on Saturday, August 31, 1799, while the Octagon was being built. Thornton even canceled a visit to Mount Vernon. He wrote to Washington that instead he and his wife "spent the day" with "John Tayloe of Mount Airy."1 Thornton did not report what they did that Saturday. Did they begin the day examining the foundation of the Octagon house and then go out to Thornton's farm to see his horses? Thornton imported two thoroughbreds in 1799 and Tayloe imported several*.

Thornton also had a reason not to go to Mount Vernon once his and his wife's day with Tayloe was done. He planned to see William Hamilton who had to return to Philadelphia "immediately." Hamilton's Woodlands had oval rooms like ones then being built in the Octagon, but he was also a connoisseur of garden plants and may have heard about Thornton's illustrations for the unpublished Flora Tortoliensis.

Thornton's letters to Washington were rarely short. In his September 1 letter, he did not pick up on the theme of his July 19 letter, no more analysis of the house rental market. Instead, he noted a letter that Secretary of State Pickering sent to the former president that the latter forwarded to the commissioners. Pickering offered a plan for the capital city's docks that would prevent yellow fever. Thornton noted that "it is a highly interesting subject and one I have urged, for three years to the board."

The

conjunction of Tayloe and Hamilton, men with oval rooms, did not

inspire Thornton to develop that theme. Instead, he noted that "the

navy- yard will be fixed... where I recommended it." He had

prevented it from being placed on the square designated for the

Marine Hospital. He also had preserved the "point" for "a

military academy, for parade-ground, for the exercise of the great

guns, for magazines, etc., etc." Then he found even higher

ground: "I am jealous of innovations where decisions have been

made after mature deliberation, and I yet hope that the city will be

preserved from that extensive injury contemplated by some

never-to-be-content and covetous individuals." Thornton clearly

had a higher mission than designing residential houses.(28)

1. Chernow, George Washington. p. 794; Brown, Glenn, "Dr. William Thornton, Architect, Architectural Record, 1896 , Vol. VI, No. 1 July-September (page 53ff)

2. Mary Carr, Thomas Wilkinson: A Friend of Wordsworth, p.11, Headley Bros., London, 1905.

3. Mrs. Thornton' s Diary, p. 90. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40066957

4. https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-first-president/george-washingtons-townhouses-in-capitol-hill

5.GW to White, 12 September, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-02-02-0471

6. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-02-02-0471 ; Harris, Papers of William Thornton, vol. 1, p. 453.

7. Anna Maria Thornton (AMT) notebook reel 3 image 40, LOC: https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss51862.001_0351_0600/?sp=40&st=image&r=-0.239,-0.129,1.22,0.454,0

8. United States Congressional serial set. 5407., #765, page 13, Hathi Trust; https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3991082&view=1up&seq=765&skin=2021&q1=Thornton

9. Thornton to GW 13 September 1796, Harris, Papers of William Thornton, pp. 395-97, WT to GW, draft letters 13 September, 1 October, draft memorial 18 November, 1796, Harris pp. 395 - 403

10. Mrs. Thornton diary, December 26, 1800, p. 225.

11.Stuart to GW 22 February 1795, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-17-02-0377; GW to White, 17 May 1795, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-18-02-0115; WT to Commrs., 10 January, 1798,Harris, pp. 430-2, 453.

12. White to GW, 8 September 1798 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-02-02-0463; Commrs to GW, 27 September, 3, 4, 15, 25, October 1798; GW to Commrs. 28 September 4, 17, 22, 27 October 1798

13. GW Diary; WT to Commrs 21 September 1798, Harris pp. 472, 475; WT to GW 25 October 1798 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0101

14. Harris p. 586 ; GW to WT, 18 October 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0076 ; WT to GW, 25 October 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0101; for contract see https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0106

15. GW to WT 28 October 1798, ;https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0108

16. GW to WT, 20 December 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0187; WT to GW 21 December, 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0189; GW to WT 30 December 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0207

17. WT to GW, 25 October 1798; GW to WT 28 October 1798

18. GW to WT, 30 January 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-02

19. GW to Commrs. 4 October 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0041 ; Commrs to GW, 4 October 1798, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/07-01-02-0008

20. GW to WT, 30 January, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-024829; 1 1 October, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0282; 1 December 1799,https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0379 ; WT to GW, 5 December 1799,https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0388; Harris, p. 515.

21. GW to Lear, 31 March 1799; https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0344

22. WT to GW, 19 April 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0375; GW to WT 21 Apeil 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0005

23. Lear to WT, 12 September 1799, Harris

24. T.B. Adams to Abigail Adams, 9 June 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-13-02-0248

25. WT to GW 19 July 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0161 ; GW to WT, 1 August, 1799,https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0180 .

26. Law to GW, 10 August 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0194 ; GW to Law, 21 September 1799, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0264

27. WT to Law, 1 August 1799, Harris p. 505

28. WT to GW 1 September, 1799, https://founders.archi(ves.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0236

1. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-02-02-0440

3. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/95860840/

4. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/cph/item/2002712363/

5. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss51862.001_0351_0600/?sp=40&st=image&r=0.334,-0.043,0.625,0.233,0

1