The Seat of Empire

A history of Washington, D.C.

Chapter One

The General and the Plan

1790 to 1801

A history of Washington, D.C.

Chapter One

The General and the Plan

1790 to 1801

In 1791 there was no room in the American dream for a cozy capital. On January 22 George Washington chose an undulating plain of well drained fields and forests along the Potomac River for the site. A few months later while sitting in his office in a Philadelphia town house near Sixth and Market Streets, from where he could almost shout to attract the attention of congressmen meeting a block away on Chestnut Street, Washington approved a plan for the nation's capital that placed the president and Congress just over a mile a part.

That seemingly inconvenient distance would allow not only buildings larger than any then extant in the nation to house the government, but it was expected that much prime real estate would fill rapidly with the seats of gentlemen and foreign embassies. And along the extensive waterfront a mile or two away there would be quays and commercial houses serving the world with American exports.

Here was a capital not merely designed to form a place of union for disparate states, but to form in itself a true Metropolis, a mother city, exhibiting all the fruits of American civilization. In 1791 the reason for such a pretense to grandeur was self-evident to most Americans. Their nation, then stretching from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, was destined to grow, and its capital destined to be a Seat of Empire, not merely the midpoint of thirteen rebellious colonies.

Most European visitors to the capital for the next fifty years couldn't help but be amused by the emptiness surrounding the government buildings. By 1799, Washington understood that he had miscalculated, and that the city's day of "eclat" would likely come in a hundred years. Washington died on December 14, 1799, and missed the city's debut when, near the unfinished Capitol, congressmen crammed into a handful of boarding houses, two to four in a room, and largely ignored in a huge, drafty mansion a mile away, President John Adams reigned, accompanied by his wife, a granddaughter, nephew and man servant.

Why did Washington get it wrong? He understood that when, by law, the federal government moved to the new capital in 1800, the 137 legislators and 112 clerks working in the federal bureaucracy would not fill the city. But Washington saw the Potomac as the route down which most American goods would stream to world markets. So a city placed just below the falls of the Potomac would soon be the nation's principal commercial city. He did not get this impression from merely looking at a map showing the Potomac so close to the West.

Growing up along Virginia tidewater, Washington was no stranger to the Potomac. For his older brother Lawrence, the river was the road to blue water and the world beyond. He served with Admiral Vernon in Bermuda, and named the home he built on the Potomac, a few miles south of the future capital, after that worthy.

Only Lawrence's death ended his efforts to get George to follow a naval career. But George's one voyage, to Barbados in 1751 when he was 19, did nothing to erase the alluring memory of his first surveying job three years earlier along the Shenandoah River which joins the Potomac some 60 miles northwest of Mount Vernon.

In 1753, just prior to the French and Indian War, Washington delivered the Virginia governor's ultimatum to the French enemy in western Pennsylvania. Washington's war experience, leading the Virginia militia in Gen. Braddock's ill-fated campaign to root the French from Fort Duquense, now Pittsburgh, not only extended his view of the Potomac and beyond, it gave him the opportunity to get a piece of the action. Soldiers who served in the campaigns against the French, as well as soldiers in the Revolutionary War, were paid in part with warrants for deeds to land in the west. Washington also bought warrants from other veterans and became the owner of some 30,000 acres in western Virginia, western Pennsylvania and southeastern Ohio.

In 1784, a year after retiring as commander of the continental army, he toured the upper Potomac again. In 1785 he became president of the Potomac Company, which he organized to build the series of locks needed to ease navigation up and down the river. James Madison wrote at the time, "the earnestness with which he espouses the undertaking is hardly to be described."

Washington wasn't alone in his enthusiasm. In the seventeenth century the Piscataway Indians prospered as they traded with whites to the south and other Indian tribes to the north. Captain Henry Fleet was taken aback when Piscataways could quote the price Canadian Indians were getting for furs.

After escaping from an attempted massacre in 1676, the Piscataways left the Potomac Valley. British colonists built three ports that would surround the future site of the capital: Alexandria in Virginia, Georgetown in Maryland, and Bladensburg, also in Maryland on what is now called the Anacostia River. The land in between seemed good for farming and in the 1770s two towns were planned not far from the future sites of the Capitol and White House: Carrollsburg, named after the powerful Maryland family organizing it, and Hamburgh, founded by Germans who, when it came time to put axe to tree and clear the land, decided to settle in Hagerstown, Maryland, richer farmland up river.

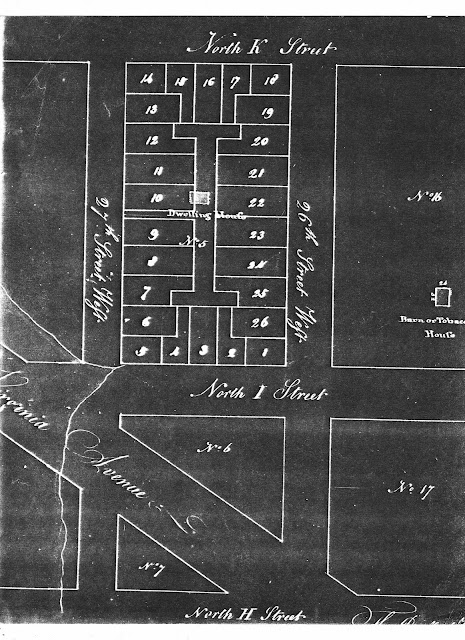

This map shows the two river towns, Hamburgh and Carrollsburg, that were never developed

Congress almost moved to the area. In 1783 a demonstration by 400 soldiers of the unpaid Pennsylvania Line prompted Congress to leave Philadelphia and convene in Princeton, New Jersey. Not a few cities and would-be cities from the Hudson River to the Potomac let it be known that they too were eager to bed and board congressmen. Congress tentatively decided to split its sessions between Georgetown and Trenton, New Jersey, but, ridiculed as a congress on wheels, changed its mind, and convened in New York City in 1785 and stayed in that very convenient city through 1790.

The Constitutional convention met in Philadelphia and mindful of the insult to Congress in 1783, by both the soldiers and Pennsylvania officials who didn't protect them from the outrage, the delegates mandated a national capital in a district of up to 100 square miles to be controlled by Congress, space enough to foster the "more perfect union" outlined by the Constitution and prove the legitimacy of the new federal government to Americans and the world. Given that George Washington presided over the convention, the certainty of his being the nation's first president, and his love for the Potomac, someone should have predicted exactly where the capital would wind up, but no one did.

The site of the capital was left up to the new Congress, which first met in New York City where the Confederation Congress adjourned. Most thought New York too far north, so promoters of the Potomac, Delaware, Susquehanna rivers, as well as Baltimore, began vying for the prize. Senator Robert Morris of Pennsylvania, thought to be the richest man in the new nation, offered $100,000 in seed money for a capital in Pennsylvania. In response, the Virginia and Maryland legislatures put up $192,000 for a Potomac site. The comforting notion took hold that the nation's capital could be built without asking Congress to appropriate a dime.

At a dinner meeting between Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, the former promised to find three southern votes to pass another stalemated piece of legislation, Hamilton's proposal that the federal government redeem at par the then almost worthless paper money the states had issued during the Revolutionary War. In return Hamilton would find northern votes for leaving New York, convening the next Congress in Philadelphia and creating a permanent seat of government on the Potomac to be ready for Congress in 1800. The temporary move to Philadelphia placated Morris and enough Pennsylvania congressmen so they would not scuttle the deal. They banked on the Potomac capital not being built.

| On July 16, 1790, the Residence Act designated the Potomac as the site of the 100 square mile federal district. However, the act left it to the president to decide exactly where on the Potomac, and where in that district to place the capital city with all the public buildings, provided that it was on the Maryland side. |

A view of Georgetown looking up the

Potomac

All the land the government needed in the District for the capital city would be deeded to the government which would then divide it into public squares, streets and house lots. The proprietors would get about $67 (25 pounds in the local Maryland currency) an acre for land the government used for public buildings and squares. Half of the house lots would be returned to the proprietor. Half would be marketed by the government. The $4 million raised from those sales, not taxes, would finance construction of the public buildings. The original proprietors of the land would be eager to cooperate because they too would profit handsomely in sales of the house lots they owned. No one thought about what might happen if the lots didn't raise enough money for the public buildings.

1200 squares divided into narrow building lots to raise $4 million for the commissioners and $4 million for a dozen or so land owners....

On January 22, 1791, six months after the passage of the Residence Act, Washington placed the ten mile square District so that it included Georgetown and Alexandria, including 1200 acres of woodland that he owned near Alexandria. He made another fateful decision on the same day: as required by the law, Washington appointed three commissioners to oversee development of the city. Thomas Johnson and Daniel Carroll were Maryland politicians and contemporaries of Washington. Thirty-eight year old David Stuart was a Virginian doctor and second husband of Martha Washington's daughter in-law. They were all slave owners. Johnson, an ex-President of the Potomac Company, had replaced white laborers with slaves whenever he could, whether building canal locks along the Potomac or at his ironworks in Frederick, Maryland.

Washington probably toured the other sites up the Potomac just to keep Georgetown land owners on tenterhooks, prompting them to offer land at a low price. Then, to finalize a formal contract, he used the same tactic. He secretly utilized agents on the scene and put them in competition with each other. One agent tried to get the best offer he could from the landowners northeast of Tiber or Goose Creek, roughly where Constitution Avenue is today, and the other agents worked the other side of the creek. (In the 17th century a Catholic landowner named Pope named his 600 acres "Rome"and the creek draining it the "Tiber," a name that took about one hundred years to catch on.)

When the principal land owner on the west side, David Burnes, wanted to reserve enough land for a farm, Washington had the man he picked to design the city, Pierre Charles L'Enfant, go down and troop around the eastern end of the city giving every appearance that the public buildings were to go there. (See Washington's letters to and about L'Enfant) That still didn't get Burnes to cooperate. At the end of March, Washington came to the city. Family legend has Burnes becoming more cooperative only after a personal interview with Washington during which the crusty Scot contrasted his gritty land grabbing with Washington's easy access to wealth via marriage to a rich widow.

Burnes cottage (erase the Washington monument in the background)

| However, tucked in a cache of family papers are documents that reveal that Burnes was made amenable by a $2,500 douceur, or bribe, from one of Washington's secret agents, Benjamin Stoddert, a Georgetown land speculator. Stoddert had benefited from both ends of the Compromise of 1790, using some of his profits from the redemption of state debts to buy federal city land. At the beginning, the city seemed awash in money. |

Late March, when Washington came to close the deal, can be dreary along the Potomac and his plan to tour the site on horseback was thwarted by rain. The next day he summoned landowners to a meeting at Suter's Tavern in Georgetown. Encouraged by the enthusiasm of the 37 year old L'Enfant whose father was a court painter in Versailles, Washington announced boundaries for a Metropolis such as Washington himself, who had been to no greater city than Philadelphia, had ever seen. In the middle of the 100 square mile district he wanted to build a city on 6,000 acres, about the extent of London at that time, which had a population of 300,000, with the President's house and Capitol over a mile a part.

It would be another two decades before people would begin calling the President's house the White House. In the early days it was usually called the Palace. Jefferson was already using the Roman term Capitol, as indeed, the meeting place of the Virginia legislature had been called since 1785. Washington promised a city plan in a matter of months. Then the streets would be cut, dividing up the city into squares which in turn would be divided into house lots, and this would be done throughout the almost six mile range of the city so that all proprietors would profit handsomely. No one raised any doubts.

In 1821 city leaders would come to blame the growing pains of the city in part on "an impenetrable marsh," but in 1791 the farms and extensive woods struck all as a promising site for a city. There was more high ground than in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore, with numerous springs and yet tolerably drained so that no one thought a new Caesar had to be summoned to drain an American version of the Pontine marshes. (The 300 or so slaves working the land didn't bother the planners and investors.)

The task at hand called more for art than engineering. L'Enfant's highly regarded renovation of Federal Hall in New York, where Washington took his oath of office and the First Congress met, showed that he had an eye for the ornate and symbolic. His work as a military engineer during the Revolutionary War encouraged the hope that he knew how to adjust to terrain.

L'Enfant above, a painting by his father below

No one questioned his regard for his new country. He had been wounded while fighting in the Georgia campaign. L'Enfant recognized the historic opportunity Washington offered him, which included the chance to design the president's house and the Capitol as well.

Before leaving on a tour of the Southern states, Washington indicated roughly where he wanted the President's house and Capitol to be, placing them in commanding position while also placating the rival factions of landowners. In the same spirit of accommodating many interests, L'Enfant placed "reservations" of public land throughout the city suitable for such amenities as a bank, an exchange, a hospital, a national church, monuments and parks throughout the city, and he connected those sites with broad avenues that cut diagonally through a grid of streets, which, he thought, would promote rapid settlement.

The March agreement provided that the government would not pay for land taken by roads. In L'Enfant's plan 55% of the land was laid out in streets and avenues. But no proprietor blanched at that, nor the unprecedented width, up to 160 feet, of some of the avenues. The pride of the nation required such magnificence. L'Enfant was also mindful of Washington's sense of the commercial importance of the city. A center piece of his design was a canal through the city allowing boats to avoid the tides and sand bars below Georgetown as they came to warehouses on the river "w[h]ere when the city is grown to its fullest extent most distant markets will be supplied at command."

When Washington returned to the city in late June, he made some changes, bringing the president's house even closer to Georgetown. He was enthusiastic about L'Enfant's angular design of the city, and ordered work to begin on the canal.

Meanwhile Andrew Ellicott, the nation's Surveyor General, finished surveying the boundary lines of the federal district, and joined L'Enfant in laying out the city. (Ellicott showed a fine sense of the opportunity presented by the project by hiring a mathematician who was a "free Negro," to help with the survey. The Georgetown newspaper noted the significance of Benjamin Banneker's participation but, nearly sixty years old, he left the arduous project in May and returned to Baltimore to publish his almanac, and thus, contrary to legend, had nothing to do with L'Enfant's plan.)

In late August L'Enfant took his completed plan to Philadelphia. The president approved but thought it premature to designate the sites of the other buildings and many monuments that L'Enfant envisioned.

Until money flowed in from lot sales, he didn't want to promise too much. He asked L'Enfant to prepare a simplified plan for engraving, then return to the Potomac and supervise building the city.

In September Washington sent Jefferson and Madison to help the commissioners at their monthly meeting make some crucial decisions. The name of the city, Washington, was made official; the District named after Columbus, recently restyled Columbia by poets and trumpeted as the "goddess" of the Republic, a fit rival for Britannia; the system of naming the streets was agreed upon, state names for diagonal avenues, numbers for north-south streets, and letters for those going east and west, (no "J Street," because in dictionaries and lists of the day that letter was still, in the Roman fashion, not distinguished from "I".) Ellicott was instructed to layout a handful of 60 by 120 feet house lots just northwest of the President's house square in time for an October auction.

L'Enfant soon had qualms about that. Since few streets had been cleared, and axemen left a chaos of downed trees, prospective buyers could not truly appreciate his plan. He thought a million dollar loan raised by the government was the best way to finance the simultaneous development of infrastructure throughout the city and along the river shore. With streets, bridges, canals, and quays built and the foundations of the magnificent public buildings dug, perspective buyers could see the true magnificence of the plan.

Meanwhile, printers in Philadelphia did not engrave the plan, perhaps, Washington feared, deliberate sabotage by people in Philadelphia who wanted the federal city to fizzle so that Philadelphia would remain the capital. Indeed, Philadelphia began construction of its own "President's house."

Philadelphia's President's house, but yellow fever epidemics in

1793, 1797, 1798, and 1799 made the rural charms of the federal

city attractive to many.

Then at the auction L'Enfant decided not to show the only copy of the plan to those attending. The bidding continued, with L'Enfant himself buying one of the 31 lots sold, but L'Enfant's antics, as well as the lackluster sales, confused and angered Washington then in Philadelphia. No one will buy a pig in a poke, he wrote to the designer.

The auction did establish the price of a city lot. Proprietors did quick arithmetic and determined that if all lots went for the average auction price of $80, they would be rich, though none could convince London bankers of that as they tried in vain to get loans to improve their property.

The meager income from the auction made the commissioners uneasy about the ambitious pace of the work L'Enfant was overseeing, and they began questioning his expenditures. That frustrated L'Enfant, who thought the commissioners and certain landowners did not seem to understand the plan. Then Daniel Carroll of Duddington, a nephew of one of the commissioners, began building a house on what was to become New Jersey Avenue. When Carroll refused to remove his half built house, L'Enfant had his crew tear it down. While this angered the commissioners, the president understood why L'Enfant did it. He scolded both L'Enfant and Carroll and told the commissioners to pay damages.

L'Enfant decided he could not work with the commissioners. His esprit de corps with his workers, none of them slaves, was remarkable. The commissioners, all slave owners, did not appreciate that and did not like the added expenses, like the "chocolate butter" L'Enfant gave to his men for breakfast. The commissioners wanted to lay off most workers until the spring, and continue construction on a piecemeal basis.

L'Enfant knew that he had been appointed by Washington and not the commissioners, that he cleared all major decisions with the president, and the commissioners who were on the scene infrequently only served to "tease and torment" him. When Washington told L'Enfant that he must work under the commissioners, L'Enfant refused. Then Washington learned that L'Enfant was showing others his plans for the president's house and did not show him, and that he was withholding his revised plan from engravers, so Washington offered him $2,000 for services rendered which L'Enfant refused and he left the project.

In discussing L'Enfant, Washington and the commissioners used language that would resonate with future historians. They described L'Enfant as temperamental, perverse, difficult and too artistic. (His probable homosexuality may have contributed to the ferocity of his critics. Click here for more on that.) Historians make much of L'Enfant's subsequent failures, an unbuilt mansion for Robert Morris in Philadelphia and unfinished canals for the Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures in Paterson, New Jersey. Little noted are the failures of the three commissioners, especially in amassing and motivating a work force. Instead of inspiring anybody, they prided themselves on hiring slave laborers from Prince Georges, Charles and St. Mary's counties Maryland to "cool" the demands of free workers.

L'Enfant's approach was reasonable, and, as difficult as fulfilling his grand plan by 1800 would be, he did envision using transparent public financing to create momentum that would attract free labor to build and live in the city. Instead Washington and his commissioners relied on the financial schemes of dubious speculators.

Washington knew that L'Enfant's leaving could destroy the momentum generated thus far, especially since the commissioners stopped all work, even on the canal. He turned to Ellicott and one of the Bostonians attracted to the auction, an eloquent young stock-jobber named Samuel Blodget, to keep the project alive. Ellicott amended the L'Enfant plan slightly and had it engraved.

Blodget dazzled the proprietors and commissioners with his schemes for financing development, but his effort to raise a private loan failed. The canal would have to wait until 1810 for digging to resume. But there were other ways to raise money. With the commissioners' blessing, Blodget created the largest lottery ever organized in America to raise money to build a grand hotel just off Pennsylvania Avenue at 8th and E Streets NW, with the hotel itself the lottery's grand prize. He planned to sell 50,000 tickets at $7 each. He broke ground for the hotel to be value at $50,000. The top cash prize was $25,000, the total amount of awards to be $350,000 including 15,000 ten dollar prizes. President Washington bought a ticket and gave it to the son of Tobias Lear his secretary. It didn't win anything. The grand prize winner, three men from Philadelphia, were not thrilled with the unfinished building they won.

But the hotel was not the building everyone was looking forward to seeing, By losing L'Enfant, Washington also lost his architect for the public buildings. So Jefferson organized an open design competition. A plan for the president's house by a 34 year old Irish builder, James Hoban, then in South Carolina, immediately pleased everyone. It replicated the grandeur of the Leinster House recently built in Dublin.

Leinster House above; Hoban's design below

It took longer to find a winning design for the Capitol. Part of the problem was that the specifications that Jefferson asked for were too small for Washington's tastes. Finally he picked a design submitted by Dr. William Thornton, a 34 year old West Indian born British gentlemen residing in Philadelphia. He received enough money from his family's West Indian estate that he decided not to practice medicine. Washington liked Thornton's large Classical dome, nothing better to proclaim the permanence and importance of the young republic.

Thornton was not qualified to superintend construction of the building which began in the summer of 1793, and first a French and then a British architect managed that. When a vacancy arose, Washington made Thornton one of the three commissioner, a position from which he could direct the embodiment of his design, much to the consternation of the trained architects doing the actual work. (Click here for more on that.)

Meanwhile, the commissioners economized by driving Ellicott out of the city. He seemed too scientific. His replacement relied more on slaves. Ellicott summed up working for the commissioners: "Neither credit nor reputation will ever be the lot of a single person who enters into their service. I dislike the place, and every day adds to my disgust."

While paying lip service to Washington's and Jefferson's hope that skilled workers could be brought in from Germany (they had to be cheaper than workers brought down from Philadelphia), the commissioners hired up to 100 slaves a year until 1799, with up to 20 or so free black and Irish laborers hired on the same terms as the slaves. Of course, the Irish kept the $60 a year they were paid; their owners got the slaves' wages. Until the commissioners decided to outsource for lumber, around 15 slave sawyers got an "extra wage" of around thirteen cents (one Maryland shilling) a day that they could keep themselves.

By paying both slave laborers and free laborers the same wage, the commissioners thought they cooled the wage demands of all workers. However, at the President's house, James Hoban and two foremen supervised a crew including their own slave carpenters who were paid less than white carpenters but more than slave laborers. Since Hoban hired four of his own slaves, every pay day was big for Hoban. Click here to see a payroll for slave carpenters.

Hoban was not married and lived presumably with his slaves in a house he built near the President's house. Several other white foremen built houses near the worksites So at least among men working on the public buildings, slavery was not necessarily like the familiar, and often toxic, plantation model where a slave master and his family lorded over enslaved men, women and children. Hoban's relationship to his male slaves was similar to indentured servitude with which many whites, especially Irish, were familiar. The slaves would not necessarily gain freedom but if they escaped, they had skills thanks to the years working for Hoban. I

The laborers served crews of skilled white stone workers and carpenters numbering about 80 men at the peak of operations. They often complained about low wages. Carpenters made about a dollar twenty a day (nine Maryland shillings.) Stone cutters made from ten to thirteen Maryland shillings a day. During the summer all workers, slave and free, worked 14 hours from dawn to dusk with a break for breakfast and dinner. But since 12 hours was considered a day, men got pay for seven days after working six. In 1797 the coordination between laborers enslaved and free and the stone cutters and stone masons was such that not one slave could be spared from the process of setting stone to make the outer wall of the Capitol. The menial chore the commissioners wanted some slaves to do had to wait.

But all the work did not go well. In the summer of 1795, to save money the commissioners replaced Scottish masons working for wages with Irish masons doing piece work. They began working on the foundation walls for all three sections of the Capitol. In June the walls laid that year fell down, all 300 feet. Because of that the commissioners decided to only build the North Wing of the Capitol by 1800 and leave the rest for later.

Fortunately, the commissioners did have the wit to pay a handsome wage to the few skilled masons who came their way, led by Englishman George Blagden.

Payroll of stone cutter, many from Scotland

The commissioners, with the president's approval, made clear that a working class was not really welcomed in the city. Skilled workers had to live in "temporary" wooden buildings, and black and white laborers in a log cabin camp. By rule all permanent houses had to be of brick. When the city opened for government business, the temporary buildings were to be torn down. The commissioners wanted residents, but gentlemen not workers. The commissioners eventually relaxed the rule but some temporary buildings were torn down. At the end of 1798, the commissioners sent most of the slave laborer's they hired back to the plantations they came from and hauled away the logs from the laborers' camp. See my blog with much more about the slave workers

Despite relying more on slave labor, the commissioners saw that they would soon run out of money. A second auction of lots, while maintaining the high price of a lot, did not generate a large volume of sales. To lubricate sales Georgetown speculators formed the Bank of Columbia. They thought they did in the nick of time because big money was on its way.

Blodget interested another speculator in the city. Twenty-eight years old James Greenleaf, another wunderkind from Boston who was reputed to have made a million dollars speculating on the American debt in Holland, approached President Washington and then the commissioners with a scheme to buy 3000 lots which would amount to one-quarter of the public lots, 3000. He wanted them for only $25 each, well below the established auction value, but he agreed to build ten substantial brick houses a year and pay the commissioners $72,000 a year for the next seven years. In December 1793 the commissioners made the deal thinking that at last they would have a regular infusion of cash and the private development that the original landowners were not carrying out.

Greenleaf was a master at smoothing his way. A secret deal with Commissioner Johnson for large purchases of his private land holdings in western Maryland (as well as a tempting offer to President Washington) helped him close the deal. Briefly the project became a focal point for visionary men. Along with architects and accountants, Greenleaf brought an inventor with a new brick making machine to speed the building of several houses near the river south of the Capitol on Greenleaf's Point, the soon-to-be commercial center of the city, just northeast of Turkey Buzzard Point. President Washington himself had just bought six lots nearby. Greenleaf also let two seasoned Philadelphia land speculators, Robert Morris and John Nicholson, join him. Although he was no longer a US Senator, the commissioners were so impressed with the legendary Morris, Financier during the Revolution, that they added 3000 more lots to the deal. The speculators were able to pay the first year's installment to the commissioners and construction began on several three story brick houses, including four known as Wheat Row which are still standing.

Then in November 1794, Greenleaf sold 455 Capitol Hill lots for $133,333 to Thomas Law, a British East India Company bureaucrat who made his fortune in India. Law also married Eliza Custis, one of Martha Washington's grand daughters. But Law's money never found its way to the city. Greenleaf and his partners had also bought six million acres of undeveloped land to the west, most in Appalachia.They counted on Dutch loans to finance all their extensive operations, but the loans failed. The French invasion of Holland didn't help. Greenleaf used Law's money to stave off his personal bankruptcy.

Before Greenleaf plunged into bankruptcy, he transferred his Washington holdings to Morris and Nicholson. Morris was Washington's close friend. The president lived in Morris's Philadelphia townhouse. In December 1795 Washington privately gave up hope that Morris could make the annual payment to the commissioners. At the same time,

Morris's reputation emboldened many in the city, including one of the commissioners, to speculate on Morris's and Nicholson's debts, in hopes that when Morris and Nicholson were flush once again, their notes would be redeemed at par; better that than letting them fail, putting titles to so many city lots in doubt.

Such scheming kept those two gentlemen afloat, but among Greenleaf's holdings was a contract to build 20 houses in one square formed by South Capitol and N Street by September 26, 1796. Failure to do so would result in a cash penalty. Morris asked to renegotiate the contract but the landowner, Daniel Carroll of Duddington, refused. So Morris and Nicholson raised around $40,000 enough to build the shells of the houses in three months just before the deadline. Then the speculators failed. Carroll got control of the houses. Many of the men building the houses got nothing. The grand plans of Greenleaf, Morris and Nicholson attracted many workers to the city. The failure of the speculators left much misery in its wake. More on early speculators

In 1795 the wife of an architect, who lost his money and sanity, raged at the speculators for creating phantom city of "dolts, delvers, magicians, soothsayers, quacks, bankrupts, puffs, speculators, monopolizers, extortioners, traitors, petit foggy lawyers, and ham brickmakers." Click here to see her letter.

Compounding the injury, the thousands of lots Morris and Nicholson owned served as security for their numerous financial transactions. So any attempt by the commissioners to reclaim title to the lots was complicated by the demands of other creditors. A US Supreme Court ruling in 1814 eventually forced Carroll to pay Carroll $39,847.87 to others who claimed ownership of the houses. (None of them are still standing.)

With the failure of the speculators, a cloud of suits threatened to obscure titles to lots. The commissioners began auctioning lots the speculators contracted to buy, but there were few bidders. All totaled lot sales raised around $6,000. Selling lots no longer seemed the sure way to finance construction of the public buildings. The commissioners also maxed out their credit the Bank of Columbia.

With Washington's blessing, the commissioners got a loan guarantee from Congress. To be sure, they offered unsold lots as the ultimate collateral -- one day they would raise at least $4 million. Thanks to congress's guarantee, the State of Maryland loaned $50,000 to the commissioners. (Not a few of the Maryland elite were or envisioned speculating in Washington lots).

The commissioners still scaled back their operations. Once the shell of the president's house was completed, they stopped work on it and concentrated on the north wing of the Capitol. This raised speculation that both buildings would not be ready in 1800 and inflamed the rivalry between land owners in the west and east ends of the city. Would congress meet in the Presiden's house or would the president move into a house on Capitol Hill?

Washington tried to mend matters between rivals by regularly staying with step-grand daughter, Martha, who married Thomas Peter, the son a major land owner in the west end, and then staying on Capitol Hill with Eliza who married Thomas Law. In 1794 Washington had bought lots in the west end of the city where he planned to build his city residence once he sold his Western lands but he accumulated enough cash from that, he changed his mind. Mindful of the need to house congressmen, during his retirement at Mount Vernon, Washington put up with the aggravation of building a large house near the Capitol. He designed two houses side by side himself and almost sent his own slave carpenters to work on them but worried that they might run away. He wound up spending around $12,000 to build the houses.

There was an obvious dearth of beds in the city. The winner of Blodget's lottery, a Philadelphia businessman, got a half finished shell of a Grand Hotel with more suits engendered by Blodget's bankruptcy than suites. That left one self-proclaimed hotel just northeast of the Capitol run by William Tunnicliffe, an Englishman,sent to the city by Nicholson and not quite bankrupt. The so-called Little Hotel was near the President's house.

Some foresaw that boarding congressmen might be the only way to survive in the city. In 1794 William O'Neale from came from Pennsylvania to quarry stone found in the city. But the insistence by the commissioners to rest every menial task on slave labor frustrated him. So O'Neale built two houses west of the President's house, failed to sell them in 1799 and opened an inn. (He soon solicited appointment as Librarian of Congress, in part to support his new baby daughter, Peggy. He didn't get the job but not a few books would be written about her.)

Even one of the original proprietors, Daniel Carroll of Duddington who originally owned most of Capitol Hill, resigned himself to building a boarding house near the Capitol. He had expected to be a millionaire by 1800. In 1797 he had built a mansion in the center of one of the squares he owned, bought an elegant carriage, but had trouble selling building lots. Because of a quirk in the contract he made with Greenleaf to buy lots, Thomas Law had been building house since 1795. He also had a row near the Capitol ready for congressmen.

Carroll's Row in the 1860s

Fortunately for the struggling city, a war broke out. Thanks to the so-called Quasi War with France, principally fought on the sea, congress passed taxes to build a navy. President Adams made the Georgetown merchant and land speculator Benjamin Stoddert his Secretary of the Navy. He saw to it that one of the new navy yards was built in Washington, even though it was 280 sailing miles to the sea.

Congress also had money to spare for the city. In 1800, the commissioners finally got another $50,000 loan from the State of Maryland to bring the president's house and Capitol to a sufficient state of completion. Congress chipped in $5,000 for furnishing the buildings and a loan of $10,000 to pave walks flanking the dirt road between the two buildings. After almost ten years of rumors that congress would not move to the city, in the end no one objected. George Washington died on December 14, 1799. In 1800 on the anniversary of his birth which fell on a Sunday people throughout the country joined processions to churches and heard a eulogium on the character of Washington.

"The people of the city and Georgetown joined to show their respect...," one diarist wrote, "but the society is too small for them to equal in pomp the other cities but they did their best -- there were about 1000 people assembled at the church." In 1800, who could spurn the City of Washington?.

But was it really a city?

The "temporary" houses for workers were allowed to stand because there was no where else for the workers to move. Four executive office buildings had been planned but only the Treasury Building, a modest brick building just east of the President's house, had been built. The government had to rent private houses in the so-called "Six Buildings" on Pennsylvania Avenue west of the President's house to provide offices for the War and State Department clerks.

The Six Buildings with a 7th added after 1800

In the summer of 1800 the federal bureaucrats packed up and moved, at the eventual cost of $48,165.57, not a few of those moving being accountants. President Adams made a brief tour of the city in June, a bit of pure politics during an election year. He needed Maryland's vote. He liked what he saw, writing to a friend, "I think Congress will soon be better here than at Philadelphia." Then he went all the way home to Massachusetts.

With the efforts of Daniel Carroll and Thomas Law, enough houses were up around the Capitol to bed and board congressmen. Conrad and McMunn, experienced innkeepers from Alexandria, turned Law's buildings into the Republican "mess." And Pontius Stelle came down from Trenton to turn Carroll's row of houses into a "hotel" that catered to the Federalists.

By all accounts the stone facades of the public buildings were impressive and the painters, paper hangers, and upholsterers were working long hours. Oliver Wolcott, Adams's Treasury secretary, moved to the city for the long hot summer. He was impressed by the public buildings and by the site of the city, which reminded him of home along the Connecticut River.

The people were another matter. William Thornton assured him that the city, where the recent census takers managed to find 3,210 people, would have a population of 160,000 in a few years. Wolcott wrote to his wife of the locals that "their delusions with respect to their own prospects are without parallel." Most of the few people living in the city were poor and "live like fishes by eating each other."

President Adams returned on November 1, 1800, and moved into the President's house. His wife Abigail joined him two weeks later.

In such a spread out city with people clustered around the two public buildings, near Georgetown, or on Greenleaf's Point, and here and there a solitary house in the vast open spaces, the city was ripe for leadership from the man who lived in the city's greatest house. Although far from home, Adams had friends who had invested time and money in the city in the city.

There was Adams' nephew William Cranch, a lawyer, who had come to the city in 1794 to manage Greenleaf's affairs. The Adams' family doctor in Washington, Dr. Frederick May, was Harvard educated, New England born, and had come to the city in 1796. Ex-senator Dalton from Massachusetts partnered with New Hampshire born Tobias Lear, former private secretary to President Washington. Dalton's son-in-law, Lewis Deblois, also from New Hampshire, was supervising construction of the Navy Yard and had come to the city since 1794 with Dalton and Lear. And don't forget Blodget and Greenleaf, both from Boston and both in the city managing on-going law suits over their failed speculations. (Cranch, Dalton and Lear also suffered bankruptcy. Adams made Cranch and then Dalton city commissioners to give them a financial boost, a $1600 a year salary.)

The Adams also got to meet the family of their son John Quincy's bride. The couple was still overseas but her parents and her sister's family lived in Washington. Her uncle, Thomas Johnson, the former governor of Maryland had been a city commissioners and was hoping to finally make some money off his investments in the city.

To be sure the Johnson's were southerners but the city wasn't that southern. A suspected slave revolt had just been crushed in Richmond but no one imagined anything like that could happen in Washington. Whites outnumbered blacks 3 to1. However, African Americas in the city claimed some rights especially on Capitol Hill where most lived. An enterprising white merchant who built a wharf and warehouse on the river south of the Capitol was miffed that the houses of Carroll family slaves in the middle of the street leading to Capitol were not removed.

In 1799 John Tayloe III of Virginia who owned 400 slaves did begin building a mansion a few blocks southwest of the President's house. The Octagon cost him $28,000 to build but he didn't make it his family's winter residence until late1801. He also supported Adams' re-election.

Jefferson, who came to town as Vice President, certainly didn't find his kind of people in the city. He boarded at Conrad's on Capitol Hill, squeezing around a dinner table for 14. He confessed to Abigail Adams that, as he walked back and forth to the Capitol, many men greeted him but he hadn't the foggiest idea who they were. (Jefferson had a high regard for the people, but not the men who represented them.)

The US Capitol in 1800 with the artist including a few men still at work though the feverish work at the time was getting the inside plastered, painted and furnished

But Adams couldn't get excited about the city, perhaps because he could not get over his envy for the man for whom the city was named. So once on the scene he only exercised his powers in improving his creature comforts. No provisions had been made for servants in his house, like a back stairs, a "necessary" with three holes, or a servant's door to the oval room. And Adams did not like some of the interior decorations, so the commissioners directed workers to "take down figures at the President's house intended to represent man or beast."

Abigail Adams made a brief career dodging leaking roofs and complaining about the need for roaring fires and the scarcity of wood to feed them. Above all she fumed at the negligence of those she had to rely on to make her house habitable. They never came on time, usually hours late. She was "amused" as she watched slaves clearing rubbish from the White House grounds but didn't object. She blamed their overseer for their inefficiency. Click here to see her letter.

With the first family settled in their spacious but damp quarters, congressmen stowed their gear at Stelle's or Conrad's and touring their new neighborhood, and according to one congressman found these conveniences: "one taylor, one shoemaker, one printer, a washing woman, a grocery shop, a pamphlets and stationery shop, a small dry goods shop, and an oyster house." Inside the Capitol, for most, the largest building they had ever been in though it was unfinished, senators found a charming, warm chamber with seats of red morocco leather.

Old Senate chamber with modern senators

Representative made do with a large room above the Senate chamber not unlike the one they left in Philadelphia. Both houses had a quorum by November 22, and on that snowy day, Adams rode to the Capitol to give his annual message.

The gathered politicians quickly put aside their present inconveniences and resumed politics as usual. They had little use for Adams. The Federalists were digesting a published attack on him by Hamilton, that, in a word, argued that he was insane, especially for sacking his secretaries of war and state, and seeking peace with France. Adams had the gall to present a treaty ending the Quasi War with France in which, with a continent waiting to be conquered, didn't win any new territory. And Adams had no friends among the opposition Republicans who blamed him for a Federalist "reign of terror" with onerous taxes and jailing government critics under the emergency sedition law inspired by the naval war with France.

Adams reminded this group of warring factions that they had to come up with some way to govern the city which the Constitution put under Congress's control. But first they debated the mausoleum, a 100 foot square pyramid to hold the remains of George Washington. Benjamin Latrobe provided a design.

In 1783 the Confederation Congress had authorized an "equestrian statue" to honor the hero, and deeming that cheaper to build, Republicans tried to substitute that for the massive mausoleum. A Federalist argued that like a pyramid, "a mausoleum would last for ages." A statue "would only remain... till some invading barbarian should transport it as a trophy of his guilt to a foreign shore."

However, the basic problem that made the mausoleum debate somewhat unreal was that the parks and squares of L'Enfant's plan had been completely neglected, most pocked with pits where slaves had made bricks or squares were carpeted by blueberry bushes. On a party line vote Congress appropriated $200,000 for the mausoleum. After the bill passed Martha Washington let it be known that she wanted the bones to stay at Mount Vernon, saving the country from the ludicrous sight of a nation building a home for a corpse in a city where there was scarcely enough buildings to accommodate the living.

Then fires at the rented office of the War Department in November 1800 and at the Treasury building in January added to the sense that here was a city doing a disappearing act, not one arranging itself to prop up monuments. That said, in joining in the bucket brigade to fight the Treasury fire just to the east of his house, President Adams left the most indelible image of his brief reign in the city.

In response to charges that the government burned the buildings to cover up thefts of government money by Federalist office holders, a congressional committee investigated and discovered the downside of using a money-saving expedient called "wooden bricks" to build a fireplace. Then before they could finally get around to creating a government for the federal district, the House had to sit in continuous session for almost a week to decide the presidential election.

The Republicans mismanaged the electoral vote and Jefferson tied his running mate Aaron Burr. (The Constitution required each elector in the Electoral College to cast two votes for president. The man getting the second most votes would become vice president.) The House of Representatives had to pick the president with each state delegation casting one vote until one candidate won nine states. Federalists controlled six of the sixteen state delegations, and Maryland and Vermont were evenly divided between the parties. If the Federalists held firm, they could force a Constitutional crisis and have the Federalist controlled Senate choose an interim president.

The Republican governors of Virginia and Pennsylvania contemplated calling up the state militias for a march on Washington, though there was no one to fight since the emergency army raised to fight the French had been disbanded in 1800.

Not a few in Washington thought there was an inevitable solution to crisis. Maryland was one of the evenly split delegations. A Constitutional crisis would ruin the federal city investments so many prominent Maryland Federalist had made. But even with its fate hanging in the balance, the new federal city didn't count for much. Through 35 ballots, the three Maryland Federalists voted for Burr, even the worthy who represented Georgetown.

The lone representative of Delaware, the Federalist James Bayard, finally gave up the fight, explaining that he could not jeopardize the future of his small state if the union dissolved over a Constitutional crisis. He also thought he had assurances from Jefferson preserving the Navy and minor Federalist office holders.

The election crisis over, there was only two weeks left to conduct business. On even numbered years, Congress adjourned on March 3, when representatives' two year term in office expired. By tradition Congress would not convene again until the following fall. As congressmen faced the prospect of leaving the city, there was no government for the District nor the City of Washington.

A House committee had investigated city affairs and discovered the commissioners nearly bankrupt and the District riven into warring factions. People in Georgetown and Alexandria, two cities of about 3,000 and 5,000 people respectively, wanted no part bearing any burden to support road building in the City of Washington. Meanwhile a newspaper published essays advocating a government for the District with a governor, a senate of 8 and an assembly of 20 until the population topped 30,000. Then there would be 16 senators and 40 assemblymen. Plus the Constitution should be amended so the city could be represented in Congress.

The Federalist controlled 6th Congress left most of that for the Republican controlled 7th Congress. But they decided they had to establish some legal system. In the Constitutional Convention George Mason had worried that the federal district would form a haven for lawbreakers from other states. Prior to Congress moving, state law still applied, but with Congress now in session, the District was in a legal limbo.

So Congress divided the District into two counties divided by the Potomac, one with the current laws of Virginia and the other with those of Maryland. That done, Congress had to provide a judiciary to enforce the laws, and along with three judges and marshals, saddled the District with 27 justices of the peace, which, legend has it, kept President Adams up until midnight making appointments of Federalist faithful, including his nephew Cranch as one of the judges.

Since he was not specifically invited, Adams left the city in the daily 4 am public coach on the morning of Jefferson's inauguration. He and the other Federalist followers of George Washington had barely fulfilled the Residence Act of 1790, and saddled the federal capital with legacies representing the worst of both sections of the divided nation: northern speculators destroyed any confidence in land values, and the use of slave labor demeaned the value of all labor. The western commerce expected to enrich the city as it pulsed through the Metropolis to the world beyond was nowhere in sight.

Emboldened by the two big public buildings, true believers in Washington's dream expected changes for the better. But, the new president, Thomas Jefferson, who had aided and abetted George Washington in all his dreaming and scheming, now thought that the meager result was just what the nation needed.

Go to Next Chapter

The City Rises, Burns, and Rises Again: 1801-1820

The City Rises, Burns, and Rises Again: 1801-1820

My new blog, William Thornton Re-examined, provides more insights into the founding of the seat of empire as well as a broad analysis of Thornton's life and work including his crusade to return freed slaves to Africa, the Patent Office, and his stint as a commissioner of public buildings overseeing construction of Capitol. Another thread throughout the narrative explores the work of those who actually designed and built the houses credited to Thornton.

No comments:

Post a Comment