Part Two: Did William Lovering Design the Octagon House?

Part Three: Would You Have Asked William Thornton to Design Your House?

My new blog, William Thornton Re-examined,

has a broader analysis of Thornton in 13 chapters including his crusade

to return freed slaves to Africa, the Patent Office, and his stint as a

commissioner of public buildings overseeing construction of Capitol.

Another thread throughout the narrative explores the work of those who

actually designed and built the houses credited to Thornton.

No one alive at the time it was built ever noted who designed the Octagon. Maybe it was too hard to keep score. Between 1795 and 1800, the number of brick houses built in the city roughly doubled from 55 to 109. Then in the next year the number almost doubled again to 207. That said, the Octagon did stick out and in 1803 had the fourth highest assessed house value in the city, $15,000. Evidently people back then didn't care about architects.

So why does everyone know now what no one back then ever wrote about? We can thank the architect Glenn Brown. Thanks to him the American Institute of Architects bought the Octagon in 1898 to serve as its headquarters. Now it is a museum with the AIA headquarters in a modern building right behind it, and, as we all know, it was designed by Dr. William Thornton.

Brown who was raised in Alexandria had a passion for Federal Period architecture. In 1888 he made drawings of the Octagon's mantels, cornices, roof truss and floor plan for American Architect and Builder News (https://archive.org/details/americanarchitec23newyuoft/page/6 ).

Brown fell in love with the house, and with its original owner Col. John Tayloe. Brown's grandfather was a senator from North Carolina and his father a doctor who served in the Confederate army for four years. Brown was raised to admire men like Tayloe who was known as the richest Virginian. Brown wrote that Tayloe, "was unrivalled for the splendor of his household and equipages, and his establishment was renowned throughout the country for its entertainments, which were given in a most generous manner to all persons of distinction who visited Washington in those days...." (He and his family lived in the Octagon only from November to May. In other months they lived on their plantation Mt. Airy outside Richmond where Tayloe worked his slaves and bred America's best race horses.) At the end of his short article, Brown said Thornton was the architect and "was a very interesting character and is deserving of a separate article."

That 1888 article failed to link Thornton's name to Tayloe and the Octagon. An 1893 article, "Historic Houses of Washington", in the widely read Scribner's Magazine extols the Octagon and Tayloe with his "five hundred slaves" and "his guests the most eminent men of his times" but makes no mention of Thornton. The one architect mentioned in the Scribner's article is Benjamin Latrobe, "the mastermind of our unequaled Capitol", for designing the Van Ness Mansion and Decatur House, the former on the slope below the Octagon and the latter on the future Lafayette Square .

Throughout the 19th century historians credited Thornton as an architect of the first version of the Capitol completed in 1828 with its noble Rotunda but modest dome. But they also credited Stephen Hallet, George Hadfield, James Hoban, Benjamin Latrobe and Charles Bulfinch. William Dunlap, a friend of Thornton’s, wrote that “He was a scholar and gentleman – full of talent and eccentricity, a Quaker by profession, painter, poet, and a horse-racer well acquainted with mechanic’s art . . . – His company was a complete antidote to dullness.” But in a three volume history of American design he published in 1830, Dunlap failed to mention Thornton's designing any private houses.

When he eulogized Thornton after his death in 1828, President John Quincy Adams noted that he, as secretary of state, had supervised Thornton for 8 of the 26 years he impeccably ran the Patent Office. "The Doctor was a man of learning, of genius, of elegant accomplishments and of very eccentric humours." Was the Octagon one of his "elegant accomplishments"? In a November 2, 1801, diary entry when the Octagon house was almost ready for occupancy, Adams wrote: "Dr. Thornton was by turns ingenious and humorous but all the time very talkative." But Adams didn't record what he talked about. No one ever reported anything he said about the Octagon.

In June 1799 Thornton talked about architecture with Thomas Adams, another son of President Adams, who was visiting Washington. Thornton had been appointed a Commissioner of the Federal City in 1794 and the President was his boss. The other two commissioners also visited young Adams. The commissioners oversaw construction of the public buildings, sold building lots and regulated private building. They took every opportunity to show President Adams, who unlike his predecessor, had never been to the city, that they had the situation well in hand and that the city would be prepared to accommodate the federal government in December 1800 as required by law.

Young Adams reported on all three commissioners in a June 9 letter to his mother. He noted that Thornton was born in Jamaica, educated in England and "a democratic, philanthropic, universal benevolence kind of a man—a mere child in politics, and having for exclusive merit a pretty taste in drawing—He makes all the plans of all the public buildings, consisting of two, and a third going up."

Actually Thornton was born in Tortola, British Virgin Islands in 1759, received a medical degree at Edinburgh in 1781 (or Aberdeen other sources say.) He designed only the Capitol not the President's house or original Treasury building flanking the President's house, which were the other two public buildings then being built. Adams probably picked up misinformation about Thornton's background from local gossips, but no one in town would have credited him for planning anything other than the Capitol. So we can take Adams' emphasis on all the planning Thornton did as a reaction to what Thornton told him about his overseeing all the public buildings. Yet in the midst of all that bragging evidently Thornton didn't mention the Octagon.

Within two years of the government's move to Washington, Congress took control of the public buildings and the city. Thornton hoped to be appointed governor of the District of Columbia (an office not created until 1871 only to be abolished in 1874) but wound up in the Patent Office. That didn't prevent him from continuing to defend his Capitol design with sharply written diatribes in the newspaper challenging changes Latrobe tried to make in the design. In none of the letters defending his reputation as an architect did he mention designing the Octagon. For example, in an 1808 reply to Latrobe's he wrote:

I travelled in many parts of Europe, and saw several of the masterpieces of the ancients. I have studied the works of the best masters, and my long attention to drawing and painting would enable me to form some judgment of the difference of proportions. An acquaintance with some of the grandest of the ancient structures, a knowledge of the orders of Architecture, and also of the genuine effects of proportion furnish the requisites of the great outlines of composition. The minutiae are attainable by a more attentive study of what is necessary to the execution of such works, and the whole must be subservient to the conveniences required. Architecture embraces many subordinate studies, and it must be admitted is a profession which requires great talents, great taste, great memory. I do not pretend to any thing great, but must take the liberty of reminding Mr. Latrobe, that physicians study a greater variety of sciences than gentlemen of any other profession . . . . The Louvre in Paris was erected after the architectural designs of a physician, Claude Perrault, whose plan was adopted in preference to the designs of Bernini, though the latter was called from Italy by Louis the 14th.So why didn't he add that he had designed Col. Tayloe's new townhouse? Or to keep his friend's name out of the dispute, why didn't he add that he had designed one of the notable new private houses in the city?

From 1801 when the Tayloes moved into the Octagon until 1828 when both Tayloe and Thornton died, Washington life pulsed with gossip. One of the best at keeping track of it was Mrs. John Quincy Adams. The Thorntons and Adamses were neighbors on F Street NW just east of 14th. She saw him frequently. In a November 22, 1820, letter to her father-in-law, she wrote:

Dr. Thornton called in late last Evening and chatted some time His conversation is indeed a thing of threads and patches certainly amusing from its perpetual variety—He is altogether the most excentric being I ever met with possessing the extremes of literary information and the levity and trifling of the extreme of folly—He is good natured rather than well principled—Mrs Adams visited the Octagon and socialized with the Tayloes, Thorntons and the rest of Washington society, but evidently no one gossiped with her about who designed the Octagon. In February 1823 she wrote to her father-in-law:

In the Evening we all went to Col Tayloes and being already out of spirits passed the most unpleasant Eveng Col and Mrs Tayloe have always lived upon the most friendly terms with my family—Their family is of the highest respectability in Virginia but among the whole of them there is not one above mediocrity in point of talents Their wealth and high standing in their own State gives them great influence and they are ever tendering proffers of their services and friendship—Tayloe's Eton and Cambridge education didn't fool her. She was born and raised in London. Plus wealth alone did not rule in Washington. Tayloe held no elected office and as a die-hard Federalist had no hope of being appointed to office by the series of Republican presidents who were his neighbors. As Mrs. Adams intimated, Tayloe tried to ingratiate himself with those in power. Col. Tayloe's racehorse Lamplighter was famous throughout the land; so why not similarly tout the name of the architect who designed his house especially if that worthy was the much admired Thornton? If the idea that the architect of the Capitol designed the Octagon intrigues us today, why wasn't that the talk of the town back in 1801? It is not uncommon for mediocre patrons to associate themselves with genius.

Quite a few people talked about the good job Thornton did at the Patent Office which he turned into a museum of inventions. Before the Smithsonian it was a must see for tourists after they visited the White House and Capitol. Maybe credit for that and the Capitol design would have been glory enough for other men, but Thornton craved more. As late as August 3, 1822, 23 years after the first president's death, Thornton complained in a letter to John Adams: "When the great Washington died, I lost a Friend, that would not have permitted me to remain so long in the back ground." He longed to be sent to South America to represent the US to revolutionary governments and also make drawings of plants. He blamed John Quincy Adams for not making him a diplomat and explorer. The urban planner and supposed architect of several buildings we still admire wished to escape from it all.

In 1896 Brown kept the promise he had made in 1888 of a more extensive article on Thornton and it appeared in the July issue of the Architectural Record (page 53ff). In "Dr. William Thornton, Architect," Brown placed Thornton in the forefront of American design. Brown provided a concise biography and also rewrote the history of the Capitol, painting Thornton as not one of many designers but its guiding genius, defending his original design from efforts by Stephen Hallet, George Hadfield, James Hoban and Latrobe, all trained architects, to change it. As Brown put it: "when Thornton was appointed commissioners, Washington requested him to see that everything was rectified so the building would conform to the original plan." Moreover, Brown argued, once Thornton was appointed to the Board of Commissioners, there was noticeable improvement in the "written proceedings and in the business forms and contracts which were introduced in connection with the streets, bridges and buildings that were in their charge." Since the improvements appeared after his appointment, "Thornton should have the credit...."

Brown listed among Thornton's private architectural works the Octagon, George Washington's two Capitol Hill houses intended for boarding congressmen, James Madison's house Montpelier, and Tudor Place in Georgetown. Brown added that he had "several of Thornton's sketches for private houses in my possession" which implied that Thornton designed several other houses.

Octagon in 1896

In promoting Thornton's reputation as a great architect, Brown did not rest. In 1900 his monumental two volume history of the Capitol appeared, published by the US government, combining lavish praise of Thornton's genius with pages of prints and photographs of the Capitol. Brown ensured the primacy of the Octagon among Thornton's house designs by persuading the AIA, then headquartered in New York, to buy it, and make Washington its new home.

Historians of the Capitol's design and construction today consider Brown unfair to both Hallet and Latrobe. To them fell the hard work of making the interior of the magnificent building work. Author and architectural historian, Pamela Scott describes Thornton as the designer only of the Capitol's exterior. Although Thornton and Brown made much of Washington's patronage, in the fall of 1794 the president needed to fill two openings for commissioners. After two men turned down the job, he appointed Gustavus Scott. Then after another turned down the job, he appointed Thornton. As for whether Brown was right to credit Thornton for making the commissioners more business-like, the other new appointee, Scott, was a Maryland lawyer who one must assume had a knack for "business forms and contracts." (In Part Three of this essay, I show that Brown had little evidence for many of his assertions.)

For the Capitol at least documentary evidence links to Thornton's role. In the case of private houses, with the exception of Tudor Place for which Thornton made extant drawings and elevations beginning in 1808, Brown's cited sources are problematic.

Today, Thornton gets no credit for Montpelier. Brown attributed it to him based on an 1830 letter by James Madison remarking: "The only drawing of my house is that by Dr. Wm. Thornton, it is without the wings now making a part of it." When Thornton visited Madison there in 1803, he made a drawing of what he saw, not of the additions Madison would build in the future.

Of George Washington's houses, Brown writes "Dr. Thornton was the architect and superintendent, as shown by letters of Washington." Today there is a plaque on the ground where they once stood saying Thornton was the architect. However, in the correspondence Brown cites as evidence, Washington invited Thornton to correct the design Washington himself made, if architectural principles required as much. Thornton offered no corrections save replacing wooden sills with stone. So Washington himself designed the buildings in consultation with the builder he hired.

As the source for Thornton's design of the Octagon, Brown cited In Memoriam, a memoir published in 1872 that collected the occasional writings of Benjamin Ogle Tayloe, the most literate of Col. Tayloe's 15 children, a minor diplomat and, like his father, a breeder of horses. Benjamin had moved into the Octagon when he was six years old. In Memoriam devotes three pages to Thornton mostly recalling "his eccentricities and the anecdotes related of him" rather than "his well-earned reputation for letters and taste." For example:

Dr. Thornton imagined he understood the science of pugilism, and complained of his being knocked down by General Van Ness, before he could assume an attitude. Their quarrel arose from a charge against the Doctor of encroaching on the General's domain,—the former claiming, by the "right of discovery," the flats in the Potomac opposite the property of General Van Ness, with the intention of converting them into an island.Benjamin Tayloe recalled Thornton's bragging on his accomplishments: "He claimed to have been the pioneer in the application of steam as a propeller for boats....Dr. Thornton told me he killed Fulton by his last pamphlet." Robert Fulton died in 1815 so that's possible. But In Memoriam includes no reports of Thornton bragging about designing houses.

Of Thornton the architect, Benjamin Tayloe wrote, "He was the architect of the first Capitol at Washington, and laid out some of the public grounds, and arranged the public buildings accordingly." He makes no mention of Thornton's designing the Octagon. Could Brown have learned of Thornton's role in conversation Tayloe's son? Benjamin Ogle Tayloe died while Brown was still an undergraduate at Washington and Lee University not yet having studied architecture at MIT. So it seems unlikely that Brown learned about Thornton's role directly from Tayloe. In Memoriam was also a source for the 1893 Scribner's article about Washington houses which didn't mention the architect of the Octagon.

The best light to put on Brown's use of In Memoriam is that since Thornton was the only friend of Col. Tayloe's mentioned in the book who was an architect, Brown assumed Thornton was the architect Tayloe employed to design the Octagon. (I have gone out on similar limbs in my own writing.) Perhaps Benjamin Ogle Tayloe was just not the type to mention the architects of private houses. In 1828, he built a house of note on Lafayette Square. In Memoriam includes an article he wrote about all his famous Lafayette Square neighbors and their houses. He didn't mention any architects.

Benjamin Ogle Tayloe house

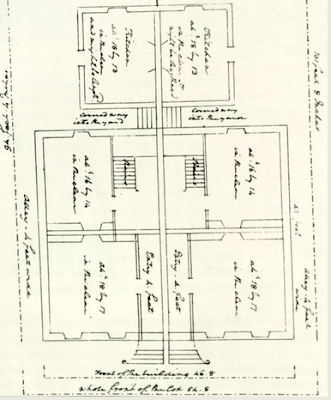

Ridout doesn't rely on In Memoriam as evidence that Thornton designed the Octagon. He points, rather, to a set of plans found in Thornton's papers.

The majority of his finished drawings have been lost, most likely consigned to the use and care of builders and project superintendents. Research is thus hampered by the surprisingly thin evidence for much of Thornton's architectural work. For the Octagon the evidence consists primarily of two unsigned preliminary floor plans... (pp. 61-62)However, the very documentary evidence that does exist could be seen to contradict Ridout's Thornton theory. The plan, as Ridout admits, "creates a sense of conflict rather than order." The other unsigned floor plan likewise doesn't match the finished house.

Ridout describes the second plan as "more carefully ordered" and suggests it was an improvement on the way to the even simpler final design. But no proof exists of their intended order.

There are two possible explanations of the drawings' origins that undermine Thornton's role in designing the Octagon.The first is that the drawings weren't Thorntons. Ridout documents that Tayloe did pay for the services of an architect. He hired William Lovering as the project's supervising architect. Ridout summarizes the recent emigrant's career after arriving from England (pp. 28-29): The extent of his training is "unclear." He was first referred to as a "contracting carpenter" and then "subsequently addressed W. Lovering, architect" and paid $1500 a year in 1795. State records list him as the designer of a house in nearby Maryland in 1798. When describing how the Octagon was built, Ridout documents Lovering's role as a supervisor of the carpenters and quotes letters Tayloe wrote to Lovering in 1801 about construction problems. Tayloe's in town agent, William Hammond Dorsey, paid Lovering a $901.60 fee on December 26, 1801 (p. 151)

Ridout also notes that in May 1800, after a year of working on the Octagon, Lovering "attempted to capitalize on his experience with the unorthodox plan of the Octagon." He advertised in the newspaper that he could provide "specimens of buildings suitable for the obtuse or acute angles of the streets of the City of Washington." (p. 123) In Part Two of this essay, I examine Lovering's career. For the moment, let's just say that if the "capitalizing" Lovering wasn't as disingenuous as Ridout implies, then one of his "specimens," some of which must have resembled the building whose construction he was then supervising, may have made their way into Thornton's papers.

The second explanation for the drawings is that Thornton may have faced the challenge of "obtuse or acute angles" not for Tayloe but in designing a house he wanted to build for himself.

Tayloe bought his lots in Square 170 in April 1797. In May 1797 Thornton too bought real estate - 20 lots at a sale of David Burnes' property including some in Square 171 just south of Square 170. He also bought public lots in 171 so that he owned lots 1 to 5 and 15 to 21, which meant he owned the east side of the square including the lot at the corner of 17th and New York which was much like the lot Tayloe built on at 18th and New York Avenue.

In 1800 Mrs. Thornton wrote in her diary (p. 102):

Saturday Feb.y 1st— a fine day. The ground covered with the deepest Snow we have ever seen here (in 5 yrs)— river frozen over.— Dr T— drawing a plan of a house to build one day or other on Sq: 171Thornton continued working on the house plan on the 2nd, she wrote, and on the 3rd Mrs. Thornton, something of a draughtsman herself, "began to copy on a larger Scale the elevation and ground plan of the House." The house was never built, the elevation lost. Could the unsigned plan now in the Thornton papers that describes a larger house be one that he drew in February 1800 for his own property in Square 171? At the end of Part Three of this essay, I return to this question, but for now, more on Thornton and how his career has been misconstrued.

Ridout doesn't mention Thornton's lots in Square 171; he takes the diary entries describing Thornton's making house plans as proof he designed the Octagon. Ridout writes: "If Mrs. Thornton's detailed diary for the year 1800 is any indication, Thornton would have been pleased to respond to the opportunity to produce a design for Tayloe, fitting it into quiet afternoons and evenings between his work routine as a commissioner." So Ridout suggests that sometime prior to May 1799 when construction began, the builder Lovering received the third version of Thornton's floor plan and never returned it to Thornton. Mrs. Thornton didn't keep a diary in 1798 or 1799, so no details can be found that way.

Mrs. Thornton's diary is essential reading for anyone interested in Washington life and society in 1800. The former Anna Maria Brodeau was 25 years old when she wrote it and had been married for ten years to "Dr. T" as she often called him in the diary. She was educated in her mother's Philadelphia finishing school, well read and literate in French. Thornton met Anna and her mother through his friendship with Dr. Benjamin Rush. After their marriage, Anna and her mother spent two years with Thornton at the Tortola plantation where he was born and which was a major source of his wealth. It was there that Thornton learned of the Capitol design contest and began preparing his entry. They returned to Philadelphia in 1793. In some brief notes on her life, Anna seemed disappointed that, rather than staying in the city and starting a medical practice, her husband moved to a farm and indulged his passion for horses. He applied to teach medicine at the University of Pennsylvania but didn't get the job. After President Washington appointed him to the Board of Commissioners, Thornton, Anna and Mrs. Brodeau moved to Georgetown. They rented a house on Bridge Street and also bought a farm in Maryland where he bred horses. In December 1796 they began moving from Georgetown to the City of Washington renting a house at 1331 F Street NW.

E Street NW in 1817

There is actually not that much in the diary about Thornton the architect, certainly not as much as we might expect if Thornton was as active in the field as his later chroniclers say he was. She briefly describes her husband designing two houses for Daniel Carroll's brother, a stables for Thomas Law, and a church for Bishop John Carroll. He also offered a plan for a rural Virginia house to Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence Lewis but the diary contains no description of his working on the design.

The client list reflects the Thorntons' propensity to socialize with everyone who counted in Washington. Mrs. Lawrence Lewis was George Washington's step-grand daughter Eleanor "Nelly" Custis. Law was married to Mrs. Lewis's sister, Eliza, and had already built several houses in the city.

Daniel Carroll of Duddington was of the family that originally owned most of the land in what would become the City of Washington. The Bishop ruled from Baltimore where he planned to build the church but didn't use Thornton's design.

The diary has enough depth that we can easily tell that the Thorntons were close to the Laws and Lewises but never saw the Carrolls. It has too little depth to give us much of an idea about what the Thorntons and their friends thought about architecture and the many houses being built around them, not to mention the finishing work on the President's house and Capitol. Mrs. Thornton does mention when Thornton worked on his design for Rotunda and South Wing of the Capitol on which work had not begun.

Or should we look at that lacuna in this way?: Mrs. Thornton's diary makes being an architect seem easy for her genius husband.

Wednesday [March] 12th: Fine day roads very bad While we were at breakfast a boy brought a Note from Mr Daniel Carroll of Duddington, - living in the City an original and large proprietor - requesting Dr T— as he had promised, to give him some ideas for the plan of two houses which he and his brother are going to begin immediately on Sq 686 on the Capitol Hill....

—Friday 14th A Warm and beautiful day Dr T— after breakfast went to the [Commissioners'] Office— returned a little after with Mr Carroll— to see the designs with which he was much pleased. (p. 116)It is easy to picture the same scene occurring a year earlier with John Tayloe requesting a plan perhaps during a stop over between his Virginia plantation and Annapolis where his wife's family lived. The Tayloes did not move to the city until late 1801 which meant he needed others to keep an eye on the project. The Georgetown merchant Dorsey oversaw payment of workers and suppliers. Lovering supervised the workers. As a friend and as its presumed architect, we might expect Thornton, too, to have kept an eye on the house.

Yet that doesn't seem to have happened. Mrs. Thornton's diary does report several visits to see the Tayloe house that didn't seem to amount to much. In her January 7 entry (p. 92) she reports: "After dinner we Walked to take a look at Mr Tayloe's house which begins to make a handsome appearance." But they didn't look inside. Sometimes Mrs. Thornton was careful to add a phrase explaining what she reported. In her January 3 entry (p. 90) she details her husband's role in the building of George Washington's Capitol Hill houses: "The money paid to the undertaker of them having all gone thro' my husband's hands, he having Superintended them as a friend." Note that she didn't say that her husband designed the houses.

That she never detailed her husband's relationship to Tayloe's house suggests he had nothing to do with it. The Thorntons took several more walks that year to see the house but she recorded no thoughts (or facts) about the house in her diary. On November 27 Thornton invited her to see the new chimney pieces of artificial stone imported from England. She was too busy tending a sick servant but found time to go with a friend to see them a week later. Almost a hundred years later Glenn Brown assumed that Thornton must have designed those fire places but in 1800 Mrs. Thornton recorded nothing about what she or her husband thought of them. (When Tayloe saw them he was enraged because the chimney piece had arrived from England without the mantels. Ridout p. 90)

Something else drew the Thorntons in the same direction as Tayloe's house, the lots they owned across the avenue. On June 26, Mrs. Thornton briefly describes what was happening on their own lots but not at Tayloe's house: "After tea we went to Mr King's to visit Mrs Tingey and Touzard — Dr T. and Mr Winstanly went with us, we walked round by Mr Tayloe's house and our lots which they have just done fencing." (p. 161)

One had best keep an eye on one's lots. On October 26 Mrs. Thornton wrote: "Mrs P. Thornton and I walked as far as Mr Tayloe's House, intended when we set out to go to Mr Knapp's, but found it too warm.— Found 4 Cattle and several Hogs in our field of buckwheat, got a little Boy to drive them out and fasten up the fence." (p. 205)

The Thorntons' interest in their lots in Square 171 could be ascribed to their desire to be across from the house Thornton designed for Tayloe opposite on Square 170. But the location held other attractions for Thornton. Inspired by the L'Enfant Plan, early publicists described how the Malls south and east of the President's house "are to be ornamented at the sides by a variety of elegant buildings and houses for foreign ministers." In 1796, as President Washington's second term came to an end, Commissioner Thornton reminded him of the need to accommodate foreign delegations. (Possibly Tayloe was drawn to Square 170 for its future proximity to embassies, but he also bought lots elsewhere in the city, presumably for investments. Houses he had built on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1818 became the core of the future Willard Hotel.)

While the diary makes no mention of her husband's association with Tayloe's house, there are entries about his ties to Tayloe's horses. Thornton and Tayloe probably became friends through their shared interest in horse breeding and racing. On April 17, 1797, two days before he paid $1000 for the lot on Square 170, Tayloe won 500 guineas (about $2000) when his horse beat Charles Ridgely's on a 4 mile course laid out just northwest of the President's house. Too bad Mrs. Thornton did not make a diary entry on that festive day. Three years later Thornton sent his prize horse down to Tayloe to face some Virginia competition.

In 1800 Mrs. Thornton made her first and only mention of Tayloe's being in the city, or at least in Georgetown. On January 24, Thornton met Tayloe at the Union Tavern where he planned to spend the night before continuing on to Annapolis. Perhaps they talked about Tayloe's house. But more likely they talked horses. In the February 16 entry (p. 108) we learn that Driver, one of Thornton's 23 horses, was "to be sent to Mr Tayloe 's in Virginia to run."

Mrs. Thornton wrote Tayloe's name exactly twenty times in her diary. Other than visits to his house and race horses the business mentioned concerned Tayloe's legal interventions on Thornton's behalf in Annapolis, where Tayloe's father-in-law, Benjamin Ogle, was governor. The Thorntons sought his help securing money owed to Mrs. Brodeau by someone in Georgetown.

The lack of any direct involvement by Thornton in building the Octagon comes as no surprise to Ridout. Thornton's modus operandi was to do no more than a floor plan and elevation and leave it to others to supervise the work. Ridout writes:

He considered himself first and foremost a gentleman and an intellectual. While architecture was not an ungentlemanly profession, the collecting of fees was pointedly disagreeable to him. Neither did he care to commit himself to the tedious work of a full-time architect directly engaged in the construction process. (p. 68)

Ridout

notes

that even when Thornton did superintend the construction of George Washington's

houses on Capitol Hill, his involvement was minimal. "The chief contractor, George

Blagden, was among the most capable and successful builders in the

region, and Thornton's duties must have been limited." (p. 61) Well,

maybe not. Thornton did visit the site and what he wrote in a letter to

Washington on April 19, 1799, suggests that he was more than an idle on-looker:

I visited the workmen the Day before yesterday, and they progress to my Satisfaction. I took the liberty of directing Stone Sills to be laid, instead of wooden ones, to the outer Doors of the Basement, as wood decays very soon, when so much exposed to the damp; but I desired Mr Blagdin would do them with as little expense as possible....While he might shun tedious architectural work, in other words, Thornton could be bossy about the building of other people's houses. In 1790 he had lived near and befriended Congressman James Madison and he jumped at the chance in 1801 to arrange for Secretary of State Madison to rent the house being built next to the house Thornton himself rented on F Street. On August 15 he wrote to Madison that he had given the builder an advance on the rent and also told him what to build:

have directed the third Story to be divided into four Rooms, two very good Bed-chambers, and the other two smaller Bed chambers. The Cellar I have directed to be divided, that one may serve for wine and c, the other for Coals and c—and for security against Fire a Cupola on the roof, which will add to the convenience of the House in other respects. There will be two Dormer Windows in front, and two behind. Our House has only one.In that letter, Thornton comes close to bragging on his accomplishments as an architect but makes a joke out of it. Thornton writes: "like Cadmus of old, after I have presumed to invent Letters for the Americans, I was sent hither to build their great City!" Thornton's 110 page book Cadmus: or a Treatise on the Elements of Written Language, by a Philosophical Division of Speech, the Power of Each Character, Thereby Mutually Fixing the Orthography and Ortoepy; with an Essay on Teaching the Surd or Deaf, and Consequently the Dumb to Speak won the American Philosophical Society's prize essay competition in 1793. On meeting any prominent man of the day Thornton gave him a copy. He titled his work after "Cadmus" because that worthy brought the alphabet to the Greeks. Then he built the city of Thebes

Then in the letter Thornton quotes a poem: "There’s a Stroke of Vanity—It lives in all my Doings!" But in alluding to his "doings" he doesn't mention the almost completed Octagon house. "...I who lately was nothing less than a Commissioner or Edile, am now reduced to a High-way Man. You will remember we are engaged in making Highways." The Board of Commissioners was in the throes of improving avenues and streets between boarding houses and public buildings. We don't know if the builder Thornton instructed took his advice.

Thornton's butting in on builders in 1799 and 1801 had no parallel in 1800. There is only one mention of Lovering who was then supervising the workers building the Octagon. On August 21, Mrs. Thornton came home to find her husband talking with Lovering. They were locked out of the Thornton's parlor and she had the only key. What could they have needed in the parlor? Thornton kept drawings of the Capitol there, which he generously showed to visitors. The Commissioners now and then hired Lovering to measure the work done at the Capitol, and perhaps Thornton wanted to show him what work should have been completed.

So let us accept that the absence of Thornton's finger prints on the Octagon's working drawings or construction bears no relevance to his genius as an architect. Let us accept that being a gentleman he was not about to brag about what he did for Tayloe. But how do we explain away this: Given his roles both as a genius designing houses in the city and a commissioner regulating all construction in the city, why when offering architectural advice did he refer to houses in London as the examples to follow? Why did Thornton hide the shining light of his architectural genius as it related to house designs?

The two houses George Washington had built side by side just north of the Capitol are the best documented houses built in early Washington. They were erected in 1799 a year when many other houses in the city were being built including the Octagon. That year Thomas Law also had a house built on the other side of the Capitol from Washington's houses, on the northwest corner of New Jersey Avenue and C Street SE. Because Mrs. Thornton mentioned Law's house in her diary and because it was built on the lot shaped by the angle made New Jersey Avenue, architectural historians think it was designed by Thornton. Its design addressed a similar problem confronted in the Octagon design.

C. M. Harris, editor of The Papers of William Thornton, writes in an introductory essay to the Library of Congress's on-line collection of Thornton's architectural drawing:

Thornton probably first suggested the idea of using a curvilinear element to take an odd-angled corner lot a year earlier [1798], to Thomas Law, who had determined to build a residence on Capitol Hill, at the northwest corner of New Jersey Avenue and C Street S.W. [sic, it was S.E.], but drawings for that project have not survived.... The two plan drawings for Tayloe's house, which became known in the nineteenth century as The Octagon, are more ambitious in their use of curvilinear forms than the modified plan to which Tayloe built.

A detail in Benjamin Latrobe 1815 map of Capitol Hill

.In Creating Capitol Hill (p. 128-9) Pamela Scott finds evidence that Thornton designed Law's house in Mrs. Thornton's diary:

In September 1798 the corner lot on the northwest corner of New Jersey Avenue (across the avenue from Law's second house) was surveyed for builder William Lovering in preparation for erecting Law's third house in the city. It was designed by William Thornton, and was "a very pleasant roomy house," according to Anna Marie Thornton.Mrs. Thornton tells us nothing about the Octagon other than it was "looking handsome" and had chimney pieces. That she went into Thomas Law's new house and was pleased suggests, to architectural historians at least, that her husband designed it.

Scott also finds evidence in a sketch Benjamin Latrobe made in a letter to a friend planning to rent Law's house in 1815.

In the caption to an image of Latrobe's letter, Scott writes "The only verified visual evidence of Thornton's design for Law's third Washington house is Latrobe's sketch of its public rooms at the apex of the acute angle at C Street and New Jersey Avenue SE." (p. 128)

She suggests that since architects like Latrobe abhorred ovals then the house must have been designed by Thornton who liked ovals. Indeed in her diary entry for January 4, 1800, Mrs. Thornton wrote: "Went thence to the Capitol, where we staid for some time by a fire in a room where they were glazing the windows —while Dr T— n laid out an Oval, round which is to be the communication to the Gallery of the Senate Room." However, Thornton didn't have a patent on ovals. In 1790 President Washington had a "two- story bow" added "to the south side of the main house" he rented in Philadelphia. A historian of that house, Edward Lawler, Jr., writes that "this is believed to have been the inspiration for other bows and oval rooms, including those of The White House."

There were no ovals in the houses Washington built on Capitol Hill. Its similarity to the Octagon and the Law house is that they were all designed and built at about the same time. If you believe Thornton designed the latter two houses, then he was associated with all three houses either as a designer or superintendent. Here was an opportunity for George Washington to get some lessons in architecture from Thornton. Indeed he invited it. On September 12, 1798, when he asked Commissioner Alexander White, a 61 year old lawyer, to recommend a builder to finish the plan Washington himself had drawn for the houses, he added: "My plan when it comes to be examined, may be radically wrong; if so, I persuade myself that Doctr Thornton (who understands these matters well) will have the goodness to suggest alterations."

White consulted with his fellow commissioners and they sent George Blagden, an English stone mason who supervised the stone work on the public buildings in Washington, to Mount Vernon and there they agreed on the specifications and plan ( httpsn://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0106 ) White and Thornton drew up a contract. Thornton was a county magistrate and notarized it.

During the process of drawing a final plan with Blagden there is no evidence that Thornton put anything on paper. He arranged for the Commissioners to give him the neighboring lot as part of the award for his winning Capitol design which for five years he "had not demanded from motives of Delicacy." He wrote to Washington that he was "willing to prepare for a House or Houses on a similar plan, the Chimnies may be run up at the same time." By sharing a party wall Washington's house would be cheaper to build. (As it turned out Thornton didn't build.) Otherwise, Thornton advised entrances to allow vats of wine to get easily into the house.

Washington also wanted a man to handle payments to Blagden for supplies and labor. All the commissioners were experienced in doing that. White didn't live in the city and Scott lived close to Georgetown. So Thornton did that service for the great man he idolized and it kept him corresponding with Washington until he died. There were more discussions of bank payments, renters and building practices than of architecture. In a December 20, 1798, letter, Washington did ask Thornton about architectural principals.Washington recalled a house he saw in Philadelphia about the same size as his with a pediment between dormer windows on the roof and "if this is not incongruous with the rules of Architecture" he wanted his houses to have the same. Thornton replied on Christmas Day: "It is a Desideratum in Architecture to hide as much as possible the Roof—for which reason, in London, there is generally a parapet to hide the Dormant Windows."

If architectural historians are right about Thornton's portfolio, presumably at that time Thornton had some idea of how such houses were designed locally. Yet he offered London as the standard. It's not like he had to reveal what he had designed for Tayloe, he could have said that he understood that Tayloe planned to have parapets on his house. If Thornton had written that we would at least know that Thornton was privy to the design -- if not the actual designer -- of the Octagon for which ground had not yet been broken. Washington thanked him for the advice, went over pros and cons and concluded that a final decision could be made later.

Tayloe's house came up in their ensuing correspondence, in the April 19th letter in which Thornton reported that he changed wooden for stone sills in the kitchen. That letter certainly presented the opportunity to talk about parapets in the design of the Octagon which had to have been finalized by then. Yet Thornton reported only that "Mr J. Tayloe of Virga has contracted to build a House in the City near the President’s Square of $13,000 value." (On April 27, 1799, Thornton personally "set out Mr. Tayloe's lot." Tayloe probably appreciated that act of friendship. The Commissioners' surveyors usually did that job. Yet had Thornton been the architect, you could argue, he might have been inclined to survey the lot earlier than four days before construction started.)

Washington did not reply to Thornton's news. He probably already knew about Tayloe's house. One can get the impression that Thornton did not know that Washington already knew of Tayloe's plans. It's odd that Thornton didn't know because Washington's involvement is woven into stories about the birth of the Octagon. Tayloe family legend has Washington persuading Tayloe to move the city, pointing out the site for the house and riding by on horseback to watch it being built. There is evidence for the last assertion. Benjamin Ogle Taylor recalled hearing from the son of a bricklayer that while he and his father were working on Col. Tayloe's house, Washington stopped on horseback and watched them work. As proof of Washington's interest in the house Ridout quotes from a February 10, 1799, letter from Tayloe to Washington in which the young builder reports that he was "anxious to appropriate every shilling I can raise towards the improvements I contemplate putting up in the Federal City." (Not necessarily good news to Washington. He had written in January hoping Tayloe would fulfill a verbal offer to buy Washington's asses and offered three for 800 pounds or around $1600.)

Thornton had another opportunity to share his thought on Tayloe's house with Washington. In a September 1, 1799, letter he explains why he and his wife didn't come to Mount Vernon as planned. "Mr. Tayloe of Mount Airy spent the Day with us." There's no mention of the house. It is difficult to believe that if Tayloe had discussions about the design of the house with Thornton that he would not have intimated the extent of Washington's influence. And work on Law's house also began in the spring and it's difficult to believe that if Thornton had designed that house, Washington would not have known. Law and his wife were frequent visitors to Mount Vernon to see Mrs. Law's grand mother, and Thornton sometimes accompanied them. That means that it is possible that Washington, Law and Thornton had thoroughly discussed houses and had no need to write about them. But you'd think Washington and Law would leave some hints in their correspondence about Thornton's designs.

Law referred to Thornton in one letter to Washington. Law was also a theatrical promoter, the city's first, and because of that hosted a glittering dinner party on August 10, 1799: "Last night I heard Bernard and Darley, and spent a very pleasent Eveng there were Thornton the Architect Cliffin the Poet and Painter, Bernard the Actor and Darley the Singer in short several choice spirits the forerunners of numbers such."

To keep a parallel with the other worthies assembled, Law had to refer to Thornton as the architect and not "my" architect. But shortly after that letter Washington came to the city and, as he always did, spent one of his nights there in Eliza Law's house and another in her sister's. In an 1800 letter Law recalled Washington's reaction when he stood in the oval parlor purportedly designed by Thornton: "General Washington was so pleased with it, that he said 'I would never recommend to a wife to counteract her husband's wishes but in this instance and I advise Mrs. Law not to agree to a sale.'"

There are no documents extant in which Law or anyone else mentions who designed or built his houses on New Jersey Avenue. Hence the importance of Mrs. Thornton's diary in determining who Law's architect was. But if we look more closely at the references to Law's house in her diary and the context of what was happening on Capitol Hill at the time, we shine an entirely different light on how his gentlemen friends regarded his architectural talents.

To begin with Mrs. Thornton's diary entry doesn't say outright that Thornton designed the Law house. Here is the complete entry from which Pamela Scott extracted a quote suggesting he did.

Sunday [January] 12th— A very fine day, as pleasant as a Spring day. After breakfast Mr T. Peter called and mentioned that his wife was at home; we therefore sent the Carriage for her. I, and Dr T— . accompanied them to the Capitol, the General's [George Washington's] and Mr Law's houses —the latter being locked we entered by the kitchen Window and went all over it— It is a very pleasant roomy house but the Oval drawing room is spoiled by the lowness of the Ceiling, and two Niches, which destroy the shape of the Room.— Mr and Mrs Peter dined with us and returned home early in the afternoon some of her Children not being well. (p. 94)Yes, Law's house was roomy but the oval parlor had a major flaw, Mrs. Thornton was suggesting. Is this a case of the superintending architect making a mistake? Or does it suggest Thornton didn't design the house? Given that Thornton seemed to lead the party into the private house through a window, one could suppose he felt he had the right of entry by virtue of his design role. And in a later diary entry Mrs. Thornton notes that Law said he liked his new house which is something you might expect the wife of its architect to note.

However another explanation presents itself. Thornton might have been emboldened to climb into Law's house through a window not because he was the designer but because he was accompanied by Mrs. Law's sister, Mrs. Thomas Peter. Both were Martha Washington's grand daughters. George Washington had died on December 14 and the trip to Capitol Hill was made to show the Peters, who lived near Georgetown, the state of Washington's houses, whose future depended on probating the great man's will, (Thomas Peter was an executor.) Thornton was also eager to get the family's approval for placing Washington's remains in a mausoleum under the yet to be built Capitol rotunda. And then they visited her sister's new house. Her older sister was rather over bearing, so criticism of her house may have been appreciated by Mrs. Peter.

The diary does explicitly refer to Thornton designing a structure for Law, but it's not a house. On March 27 Mrs. Thornton writes: "Dr T. received a Note from Mr Law enclosing a rough Sketch of a plan for his Stables behind his House which is five Stories behind and three before, which Dr T — promised to lay down for him, as he had suggested the ideas—" That night he got to work on the plan. "The Stables and Carriage house are to be built at the bottom of the lot and the whole yard to be covered over at one Story height, and gravelled over, so as to have a flat terrass from the Kitchen Story all over to the extemity of the lot.— I wrote a note to Mrs Law excusing our dining with them tomorrow—the weather appearing very threatening—."

This is confusing. Thornton suggested the idea, then Law made a rough sketch, and sent it to Thornton who made a plan. Finally Mrs. Thornton expounds on an architectural topic no doubt relaying her husband's ideas. But it is about stables. There were not a few stables built in early Washington including one next to the President's house. Architectural historians don't credit Thornton with designing any stables. They credit Lovering for designing the stables at the Octagon.

When congressmen came to town in December 1800, Law leased his new house and a neighboring building to Conrad and McMunn for a boarding house. They advertised "stableage sufficient for 60 horses." Yet Thornton gets no credit for that singular achievement.

But why did those stables generate such excitement back in March between Law and Thornton? Plus two weeks earlier Daniel Carroll had asked for a design for two houses. Those houses built in the middle of a block presented no architectural challenge. His brother Henry Carroll, who financed the building, put them up for sale in early 1801 and described them as "finished in a plain but substantial manner and built of best materials." Thornton's plans must have been no more daring than the typical builder's plans. Why was the gentleman architect who made designs for great and challenging buildings suddenly designing a humdrum town house and stables? One can't help getting the impression that rather than being sought out for solutions to the relatively difficult architectural problem of building spacious townhouses on angled lots or designing houses worthy of the gentleman who designed the Capitol, Thornton was simply a fount of ingenuity volunteering ideas in the heat of conversation and congenial to putting them on paper if asked.

On December 13, 1799, Commissioner Alexander White wrote a private letter to President John Adams that amplified on an assurance made in an official letter from Commissioners White and Thornton (two commissioners together could do official business) "that a good house in a convenient situation may be provided at the seat of Government for the use of the President until that intended for his permanent residence shall be finished." In his private letter White revealed that "the houses alluded to were, One building and in great forwardness near the Presidents Square, by Mr Tayloe of Virginia, and two new houses built by Mr. Carroll and Mr Law, near the Capital—Any one of these three is better than the President of the U. States, as such, has resided in—." (https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-4080 the editors of these on-line papers transcribed "Taylor" but the letter clearly reads "Tayloe.")

Adams told his Secretary of the Navy what White wrote. Benjamin Stoddert who was also a Georgetown merchant wrote to the Commissioners that Adams insisted on moving into the President's house. The commissioners received the letter on January 7. (Is that why the Thorntons took a walk to look at the Tayloe house that day?) The other commissioner Gustavus Scott who lived near the President's house wasn't amused and Thornton joined him in disavowing what White wrote: "We hold it highly dishonourable to violate that faith which was pledged to the City Proprietors when they relinquished their property for a City—." There was no way the commissioners could countenance both branches of government being placed on the same side of the city.

President Adams' orders didn't settle the issue. Abigail Adams didn't like what she heard about the new President's house and told friends that she was not sure she wanted to spend the following winter in the large cold house. Once they heard about her concerns both Thomas Law and Daniel Carroll tried to lure the First Family to their houses. On April 9 Law wrote to James Greenleaf describing his house. That reforming bankrupt was in Philadelphia and had a family connection to the First Family. His sister was married to their favorite nephew, William Cranch, who once was Greenleaf's clerk and then did legal work for Law. The idea was for Greenleaf to get the letter or at least the information in it to Abigail Adams.

Carroll evidently learned about Law's scheme and wrote a letter of his own for Cranch to give to his aunt and uncle. On April 26 Cranch enclosed Carroll's letter in his own and opined that Carroll's house, Duddington Manor, was the better house. It was farther down New Jersey Avenue and had a whole city square to itself. In his letter Carroll boasted that it had "one of the best springs in America." As for the house itself, Carroll took pride in its being "finished in a plain decent style." Cranch preferred it to Law's house because it was farther from the marsh at the foot of Capitol Hill and Mrs. Carroll was cordial to Mrs. Cranch. Evidently the sometimes imperious Mrs. Eliza Custis Law did not notice Mrs. Cranch.

All those letters wound up in the Adams Family Papers so it appears Abigail Adams at least received them. John Adams respected his wife's worries enough to postpone a final decision. In June, he went to the city himself and found it and his house to his liking. He had seen the palaces of Europe and thought the American president deserved the same. (Carroll asked $2000 rent, Law half that. A cynic might suggest that President Adams' interest in the new capital was principally that it would accommodate him rent free.) He moved into the Palace, as it was often called, in October, Abigail joined him a month later.

Is it possible that while trying to lure the First Family, Law and Carroll also competed for the favor of Commissioner Thornton reasoning that he might have some say in choosing a private residence for the First Family? He and White had first floated the idea after all. White, though, after his colleagues attacked him for identifying the houses, retreated to his home in Virginia. The other Commissioner, Scott, was dying of cancer. This left the eccentric genius Thornton in charge. Which side was he on? So asking Thornton for designs of an ordinary house and stables on Capitol Hill could be viewed as a salvo in the battle for Adams' favor. In 1798, when asked where to put the executive office buildings of the government, Adams opined that putting them next to the Capitol was fine with him. Such presidential whimsy is what Law and Carroll hoped to kindle once again..

The rivalry between the East and West sides of the city was as old as the 1791 decision to build the capital between plantation owners in the east and Georgetown merchants to the west. The rivalry only got worse as the years passed. In a February 4, 1797, letter to President Washington, Thomas Law complained "I aver that When Mr Young, Carroll myself and other Proprietors near the seat of Congress waited upon Mr Scot to approve a Petition to the Legislature of Maryland for a Bridge over the Eastern branch, he amused us by shewing the Presidents House on the Map and by pointing out where the Offices should be and by anticipating the future splendor of that part of the City by the residence of Ambassadors and by the Assemblage of Americans who were great Courtiers."

Three years later in her diary Mrs. Thornton related a report that people in Georgetown expected congress to meet in the President's house. That she hoped not, would have surprised people on Capitol Hill who nursed suspicions that Thornton favored Georgetown. The farm he bought lay west in Montgomery County, Maryland, neighboring that of Georgetown's Benjamin Stoddert. In 1799 Thornton opined that if yellow fever drove the government out of Philadelphia, congressmen could live and meet in Georgetown College. If in the 1800 merry-go-round of social visits for tea, as word got around that Thornton was designing his own house on a lot across the street from Tayloe's, Law and Carroll may have felt desperate and cheated. Law and Notley Young, Carroll's uncle, had helped Thornton acquire the lot next to Washington's houses where he promised to raise a party wall to reduce their mutual expenses. That's where Law and Carroll wanted him to build and raise property values.

Since he didn't take money for his designs, asking Thornton for a design was not a bribe, but it was flattery. Of course, this explanation for why in March 1800 Law prevailed on Thornton to design his stables assumes that Thornton didn't design any of Law's houses. Indeed, if he had, merely heaping praise on his designs might have been flattery enough. Then again, given the opportunity, why not associate the designer of the Capitol with the house you're offering to the First Family? Law did not. His letter to sway Mrs. Adams lauds the house in great detail with no mention of who designed it:

The house I occupy is built upon the side of an hill - the lower story has two cellars and a passage to the outhouses. The kitchen story has an excellent office abt 21 by 20 which contains a folding bed and 4 windows, a store room, a pantry and the best kitchen in America - in the area is the ice house filled - the kitchen is in the form of a fan thirty six feet across with dressers and a modern kitchen or fire to boil, bake, and c. On the ground floor there is a handsome oval room 32 by 24 and a room adjoining 20 by 28 - the oval room is so handsomely furnished that I wish to leave the eagle round glasses, carpet and couches in them as they are suited to the room - above stairs is a dressing room and a bedroom 21 by 20 - a center room with a fireplace about 17 by thirteen, an oval room 30 by 25 - and a room 20 by 11 with a fireplace - the same upstairs - say 8 bed rooms or 7 bedrooms and an oval sitting room. The fireplaces in the large room have marble.

It is the most convenient house I ever was in the view is beautiful - it is dry - has an excellent pump of water on the hill which goes to the kitchen - it is most dry, in short the President cannot be better accomodated - it has a stable for five horses, a good coach house, hay loft etc etc - no one can be but pleased with it. It is warm in the winter and cool in the summer having all the southerly wind. General Washington was so pleased with it, that he said "I would never recommend to a wife to counteract her husband's wishes but in this instance, and I advise Mrs. Law not to agree to a sale"....

Thomas Law's sketch of his kitchen

By associating "Architect Thornton" with this wonderland of ovals, Law would have flattered Thornton and could have gratified architectural historians of the future by linking ovals and curvilinear designs to fit an angled lot.But since Thornton designed the Capitol, wouldn't he have been partial to that part of town already? Why would Law have to use flattery to entice him there? Thornton developed a curious relationship with the Capitol which will be a topic for Part Three of this essay. Briefly put, he was incapable of providing or found it too tedious to provide the drawings needed by workers. The most complex and largest structure yet built in America needed a lot of working drawings. So, being too close to the building would only subject him to frequent embarrassments. He rented the F Street house as his residence because it was nearer the Commissioners' office. To ensure his separation, he even asked work supervisors to send their requests for instructions to the Commissioners; office. For example, on October 24, 1796, when Blagden needed to know if and how the pilasters would "diminish", he had to write to the Commissioners. Thornton wanted to be asked about the Capitol's design in writing. He did not want to be buttonholed and asked to explain what he intended in person, in front of workers, .

By 1795 it was widely known that the interior of the Capitol as designed by Thornton would have inadequate head room. That led to this insult: "He has his head to clear of the lumber which crowds it to make room for what is correct." ( https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-18-02-0175 note 3) But joking aside, thanks to his role as Commissioner Thornton had power enough to preserve his designs (and reputation.) With the support of just of his fellow commissioners, who knew little about architecture, he could officially check any effort by supervising architects at the Capitol like George Hadfield and James Hoban to change his design and have it stopped in writing so posterity would know whose design it truly was. That cumbersome process of policing the men trying to get the work done could try the patience of his colleagues who must have wondered why architect and builders couldn't simply talk to each other. Periodically they sided against Thornton, also in writing.

On April 17, 1799, (two days before Thornton wrote to Washington about Tayloe's house contract) his fellow commissioners wrote to Thornton reminding him that the 1793 advertisement for the contest to design the Capitol required that the "Author should furnish the necessary drawings." They informed him that the Superintendent of Capitol construction, then James Hoban, asked them "for several drawings of the sections of the Capitol without which he cannot progress with the building." Thornton replied that he was "on the spot" to give advice, that since the work then being done was temporary he didn't make drawings, and, come to think of it, the job description of the superintendent included making drawings.

I estimate Thornton's avoidance of the Capitol building delayed construction by a year. The point to make here is that, in the crucial days of early 1800 when uncertainty prevailed about what would happen when congress arrived in December, Law and Carroll did all they could to flatter Thornton.

Given that, and the rivalry between the East and West sides of town, why was there no flattery from the likes of Stoddert and Tayloe who had bet on the west side of town? Simply put, Thornton might be in charge but Stoddert controlled the flow of money. (I won't go into whether Tayloe flattered Thornton by taking one of his horses seriously. There is no record of one of Thornton's horse ever beating Tayloe's.)

Congress had been financing the public buildings in one way or another since 1796 and never had much confidence in the Commissioners. So in January 1800 they appropriated $10,000 to prepare the city for their coming and ordered the cabinet secretaries to dispense it. In that function the secretaries of State, Treasury and War deferred to the Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Stoddert, Georgetown merchant, speculator in Washington lots and owner of the farm neighboring Thornton's.

If not Thornton, who did design the Octagon? Part Two of this essay explores who was designing and building other houses in the city and focus on William Lovering. Compared to Thornton, he suffered the disadvantage of not being a gentleman. He had to offer his services in newspaper ads, not during tea or dinner. He worked for his living and was not celebrated for any other attainments or, as far as we know, ever held any position outside the building trades. Put it this way: Thornton corresponded with Washington, Jefferson and Madison and dined frequently with all three, and with Tayloe, once Tayloe moved to the city. Lovering wrote one note to President Jefferson about a "Mangle" he "made for Callendering of Linen" that President Adams' servant requested. Jefferson wasn't interested.

However, in 1798 Lovering claimed that he superintended the construction of two-thirds of the houses in the city. No one doubted that since they were all still standing including several impressive brick buildings on Greenleaf's Point . Much of southwest Washington below the Capitol was named after James Greenleaf, the speculator who first hired Lovering. How could a gentleman who wanted to build a house ignore Lovering?

To be fair to Thornton what can't be explained away is his knack for drawing up plans all the more impressive because he wasn't a trained architect. His drawing also impressed men known to be careful judges and particular in what they wanted, namely Washington and Jefferson who were so enthusiastic about Thornton's original elevation and floor plan for the Capitol.(Neither the originals nor copies remain.) When Thornton bragged on himself in his 1804 reply to Latrobe he highlighted what he thought important in architecture: ancient masterpieces, the orders of architecture and "the genuine effects of proportion [that] furnish the requisites of the great outlines of composition." His Capitol design was a great outline in composition.

The drawings and photos Glenn Brown used in his 1896 article to illustrate the Octagon by contrast show little of "the great outlines of composition exhibited" in Thornton's Capitol design. To illustrate Tudor Place, Brown used Thornton's floor plan and also a contemporary drawing made in 1894 by a member of the owning Peter family.

Artist Walter Gibson Peter was himself an architect

The drawing strikes one as something that Thornton, with his "pretty taste for drawing" could have done himself. When designing Tudor Place on a hill above Georgetown, Thornton had enough space to proportionally balance the needs of a private residence with a tasteful classical focus. The building lots confining the designs of the Octagon, the Law house and any other private house in the city did not inspire Thornton. What was the point of laying out an oval room in a building that due to the constraints of practicality and economy required ceilings too low to accommodate it? In her diary, Mrs. Thornton expressed the contradiction when she saw Law's house. It was roomy but too cramped for grandeur. Conceptually linking the curvilinear fronts of the Octagon and Law house and crediting Thornton for both, as architectural historian do, is ingenious use of scant evidence, but Thornton preferred his ovals to be grand and preferably under a dome.

Thomas Jefferson understood Thornton's strengths and limitations as an architect. On May 9, 1817, he enlisted Thornton's aid in filling a large quadrangle with buildings to form the core of the University of Virginia: "Will you set your imagination to work and sketch some designs for us, no matter how loosely with the pen, without the trouble of referring to scale or rule; for we want nothing but the outline of the architecture, as the internal must be arranged according to local convenience. A few sketches, such as need not take you a moment." (https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-11-02-0284)

Jefferson understood that Thornton was an outline of an architect. In his reply, Thornton was in his element:

I admire every thing that would tend to give chaste Ideas of elegance and grandeur. Accustomed to pure Architecture, the mind would relish in time no other, and therefore the more pure the better.—I have drawn a Pavilion for the Centre, with Corinthian Columns, and a Pediment. I would advise only the three orders: for I consider the Composite as only a mixture of the Corinthian and Ionic; and the Tuscan as only a very clumsy Doric.In this letter, Thornton finally shares architectural insights with a former president based on his own experience with a house he designed, not the Octagon but the Lewis house. He describes how its columns were made:

Columns can be made in this way most beautifully, as I have seen them done at mr. Lewis’s, near mount Vernon, where they have stood above 12 years, and I did not find a single crack or fissure. The Bricks were made expressly for columnar work, and when they were to be plastered, the Brick-work was perfectly saturated with water which prevented the plaister from drying too rapidly.—The mortar was not laid on fresh. It was composed of two thirds sharp well washed fine white sand, and one third well slaked lime. I would mix these with Smiths’ water. I would also dissolve some Vitriol of Iron in the water for the ashlar Plaister, not only to increase the binding quality of the mortar, but also to give a fine yellow Colour—which on Experiment you will find beautiful and cheap. (Remember Thornton had a medical degree.)In her diary entry for August 4, 1800, 17 years earlier, Mrs. Thornton describes their visit to Mount Vernon and the nearby Woodlawn site, a wedding gift from George Washington to his step-grand daughter Eleanor "Nellie" Lewis:

Dr T. and Mr Lewis play'd at Back gammon till tea. After breakfast— Mrs Lewis, the young Ladies and I went in Mrs Washington's Carriage (a Coachee ; and four) and Mr Lewis and Dr T. in ours, to see Mr Lewis's Hill where he is going to build— and his farm and mill and distillery. Dr T. has given him a plan for his house.— He has a fine situation, all in woods, from which he will have an extensive and beautiful view.In the eventful year 1800, that was probably Thornton's happiest day.

Part Two: Did William Lovering Design the Octagon House?

Bob Arnebeck

(I am very grateful to Mandy Katz for copy editing and editorial help; opinions expressed all my own,)