I have created blog re-examining Thornton's work as as architect. Here is link to the table of contents of the blog which is organized as a seventeen chapter book:

https://ingeniousa.blogspot.com/2023/01/table-of-contents-case-of-ingenious-a.html

Would you have asked William Thornton to design your house?

As of 1799, the US Capitol was the only

building in Washington that Dr. William Thornton was known to have had a role in

designing. But it was notorious that his original

1793 design was not buildable. Controversy about that flared up again in 1799. Yet Thornton was a formidable influence on the city's

architecture because by attacking changes professional architects

made to his Capitol design, he became the city's first architecture critic.

He defended his own design and attacked others with considerable

rhetorical skills including references to buildings and houses in Europe.

He had added influence

because as one of three Commissioners overseeing the city's

development, he had power over what happened in the city. That power

was largely undefined. For example, there was no formal process of

approving house designs, but Thornton boasted

of doubling the sale price of lots to block construction of a row of houses on Capitol Hill because

the design "was destitute of taste and loaded with finery."

So apart from evidence noted in Parts One and Two of this essay, there are two other

factors to weigh before deciding who designed the Octagon. Given the

continuing controversy over Thornton's Capitol design, was it wise to

ask him to design a private house? Then again, given Thornton's

rhetorical command of architecture and his power as a Commissioner,

was it wise to ignore him?

Ironically the man who chose

Thornton's design of the Capitol in 1793 and who appointed Thornton

to the Board of Commissioners in 1794 faced that dilemma in 1798. George

Washington had to decide how much to involve Thornton in his own

building project. Analyzing the ample evidence of how Washington

handled Thornton might help us understand what Thornton's influence

on the Octagon design process might have been. That was a process

about which we have meager evidence.

George Washington spent $12,000 to build the two houses with the double doors. Admiral Wilkes bought the houses for $4000 in the 1830s. In the 1840's Wilkes returned to the city and found the side of the hill dug out for gravel to be used for walks around the Capitol.

In September 1798 when

Washington decided to build two houses on Capitol Hill, much had

passed between him and Thornton since 1793. The plan Thornton

submitted in the Capitol design contest was a godsend that quickly

turned into a nightmare. Washington had originally planned to have

L'Enfant design the Capitol and President's house. In March 1792

after having only made his plan of the city, L'Enfant left the project. Washington

had the Commissioners announce a design contest for each building with a $500 prize, plus a lot

in the city for the winning Capitol design. In July 1792, James Hoban, a 30 year old Irish architect who since 1787 had

been designing and building houses in Charleston, South Carolina, marked out the lines of the President's house. Washington was

at his side making sure the house was bigger than Hoban's winning contest entry design.

A French architect, Stephen

Hallet, who had recently left Paris for Philadelphia, almost had a

winner for the Capitol but Washington was not moved by his entry. The

Commissioners let Hallet move into a house in the city hoping he would come up with revisions to please the president.

Washington feared that not

building the Capitol and President's house at the same time would

excite the rivalry that already existed between the East and West

ends of the city. Still, Washington had the Commissioners reopen the

design contest for the Capitol. That gave Thornton the chance in

January 1793 to submit a design which he had “worked on night and

day” during his extended honeymoon on his family's plantation in

the Virgin Islands. He had left the island of Tortola when he was 5 years old

to be educated in Britain. After getting a doctorate in medicine in

Scotland, Thornton decided to make his career in Philadelphia where

in 1790, the 31 year old doctor quickly made a sensation with an essay on language, an

award winning design for the Library Company of Philadelphia's new

building, and his marriage to the 15 year daughter of the

headmistress of the city's premiere finishing school.

For the rest of his life upon meeting another influential gentleman, Thornton gave him a copy of his prize winning essay. That gentleman could not help being impressed

Both Washington and his

right hand man in the Capitol project, Secretary of State Thomas

Jefferson, were taken “by the beauty of the exterior and the

distribution of the apartments.” Thornton

went to Georgetown to deliver his plan. Directed by the enthusiasm in

Philadelphia, the Commissioners awarded Thornton the $500 prize and asked him to lay out the foundation as soon as possible. He surprised the Commissioners by suggesting they ask an

architect to do it. He also didn't have any idea

how much his design would cost to build.

The two architects already employed by the Commissioners, Hallet and Hoban, warned the Commissioners, and then both Washington and Jefferson when they passed through Georgetown, that Thornton's design was far too expensive and, as designed, parts of it could not be built. Both the president and Commissioners had pledged themselves to grandeur for the ages despite the expense but....

The two architects already employed by the Commissioners, Hallet and Hoban, warned the Commissioners, and then both Washington and Jefferson when they passed through Georgetown, that Thornton's design was far too expensive and, as designed, parts of it could not be built. Both the president and Commissioners had pledged themselves to grandeur for the ages despite the expense but....

On June 30, 1793, Washington asked Jefferson to arrange a meeting with Thornton and his critics, adding:

“It is unlucky that this investigation of Doctor Thornton’s

plan, and estimate of the cost had not preceded the adoption of

it;... I had no

knowledge in the rules or principles of architecture—and was

equally unable to count the cost.”

To be fair to Thornton, Washington

asked Jefferson to convene the meeting in Philadelphia where Thornton

lived and planned to practice medicine. Plus Thornton could invite

two builders to the meeting to defend his design. Jefferson also sent

Thornton “five Manuscript Volumes in

folio” (20 pages, which have been lost) in which Hallet attacked Thornton's design. In Thornton's

papers there is a draft of a letter of just over 2000 words long in which Thornton defended his design. He sent the final version to Jefferson.

Judging from Thornton's reaction,

Hallet exhausted himself challenging (in his second language) the

details of Thornton's design. Thornton admitted being frustrated by

not having a copy of his design and by Hallet's bad handwriting.

Thornton admitted to a few mistakes and then set out to prove that he

knew more about architecture than the French architect. In his letter

Thornton referred to the Ancients, the Escorial, the Louvre, and he put

the Capitol in context: “It is

but of small magnitude when compared to many-private Edifices of

Individuals in other parts of the World.”

Detail of 1722 painting of El Escorial by Houasse

That this huge royal complex in Spain took 21 years to build was a fact Thornton thought relevant to construction of the Capitol

That this huge royal complex in Spain took 21 years to build was a fact Thornton thought relevant to construction of the Capitol

Hallet had a motive for attacking

Thornton. Well aware of the excitement generated by Thornton's

design, he sent a written description of his own latest design to Jefferson.

Thornton did not impugn Hallet's

motives but did fault him for making so much of mistakes that could

be easily corrected, such as the placement of the columns to support

the dome. But he doubted Hallet's qualifications to criticize the

essence of his design:

The want of unity between the Ornaments and the Order, forms another objection in Mr. Hallet’s report. I trust he will permit me in this instance to prefer the authorities of the best books.... The Intercolumniation of the portico is objected. The Ancients had five proportions, (viz) the Picnostyle containing 1½ Diameter; the Sistyle 2 Diameters; the Eustyle 2¼ Dia:; the Diastyle 3 Diam:; and the Aræostyle 4 Diameters. The Eustyle is reasoned the most elegant in general, but deviations are allowed according to circumstances,....

One of Hallet's many plans

"poor Hallet, whose merit and distresses interest every one for his tranquility and pecuniary relief"

Jefferson lamented in a February 1, 1793, letter.

"poor Hallet, whose merit and distresses interest every one for his tranquility and pecuniary relief"

Jefferson lamented in a February 1, 1793, letter.

Then they all met, the President attending as long as he could. The

better known of Thornton's experts, Thomas Carstairs, saw the

problems with Thornton's design, and his other expert, a Col.

Williams, appeared to agree. All agreed that changes that Hallet made

to Thornton's design were better and cheaper. Then the day after the

meeting, Williams called on Jefferson and explained that conferring

with Thornton, he thought all objections “could be removed but the

want of light and air in some cases.” Jefferson was very skeptical,

telling Washington that Williams' “method of spanning the

intercolonnations with secret arches of brick, and supporting the

floors by an interlocked framing appeared to me totally

inadequate;... and a conjectural expression how head-room might be

gained in the Stairways shewed he had not studied them.”

No rival of Thornton's would forget the

trouble with the headroom.

In his July 25, 1793, letter to the Commissioners, the President described the agreed upon design as “the

plan produced by Mr Hallett,” but it preserved “the original

ideas of Doctor Thornton, and such as might upon the whole, be

considered as his plan.,..” And then he goes

on to say: “Mr Hoben was accordingly informed that the foundation

would be begun upon the plan as exhibited by Mr Hallett, leaving the

recess in the East front open for further consideration.” Hallet thought Thornton's grand portico entrance with the elliptical front

and grand staircase would block lighting and

ventilation in the North and South Wings. In August, the President sent the

Commissioners the cost estimates Carstairs made for the stone work on what the President called “Hallet's

plan.”

We now don't exactly

know what plans everyone was looking at because they no longer exist. By the way the Dome was not Thornton's

original idea. Samuel Blodget, a land speculator who replaced

L'Enfant as superintendent of all work in the city, sketched out a Roman edifice with a Dome before Thornton submitted his design.

The cornerstone of the Capitol was laid

on September 18, 1793, and during the public ceremony Thornton was

not recognized in anyway. Hoban and Hallet were both listed as its

architects. During the winter Hallet concentrated on completing

designs of sections of the huge tripartite building. Hoban shifted

masons who had finished the wall of the first story of the

President's house over to lay the foundation of the Capitol. No one

asked Thornton for any advice least of all the Commissioners who

recognized that the President made all the decisions about it and

that their job was to raise money and hire workers as cheaply as

possible.

Meanwhile on November 29, 1793,

Thornton solicited appointment as Washington's secretary. He admitted to him

that “My Situation in Life has precluded me from the honor of being

but very partially known to you...,” and offered James Madison who

he had befriended in Philadelphia in 1790, as a reference. Neither in

Thornton's letter nor Washington's brief reply (he had appointed

somebody else) was there any mention of the Capitol.

Was Thornton being shunned for

submitting a deceptive design and then trying to back it up with an

incompetent expert? It is unlikely that Washington thought that badly

of a young man everyone thought congenial and informative. The

Commissioners soon got

some use out of Thornton, at least out of his “ideas.”

As the foundation continued to rise in

the early summer of 1794, Hallet gave orders to the masons which

angered the head mason, a Scot named Collen Williamson, who

complained to the Board. The Board had hired Williamson in 1792, and

he won their gratitude by laying the founding and building the first

story of the President's house. (But he was old and ever claiming

that the stone castles he built in Scotland were better than the

brick-infused buildings in Washington and was eventually fired.) He

intimated to the Board that the drawings Hallet was using were

different than what the President had sent down from Philadelphia.

The Board asked Hallet to give them all his drawings.

Hallet had not exactly prospered. When Jefferson learned that his wife and children lived in poverty in

Philadelphia, he was quite alarmed. When they moved to Washington, three children died. Maybe that's why Hallet overreacted to the Board's

demands. He said he would give the drawings up only after they hired him as

superintendent of construction, which paid $1500 a year, and credited

him as the only designer of the Capitol.

Hallet replied on June 28 that he believed the earlier conference had led to the adoption of his plan: “In the alteration I never thought of introducing in it any thing belonging to Dr Thornton’s exhibitions. So I Claim the Genuine Invention of the Plan now executing and beg leave to Lay hereafter before you and the President the proofs of my right to it....”( see footnote 7)

The Commissioners fired Hallet. The speculator James Greenleaf took up his cause and kept him at work refining his Capitol design as an insurance policy in case the Commissioners' maladministration delayed construction of the Capitol.

At the same that they dismissed Hallet, Commissioners Thomas Johnson and David Stuart announced their retirement – they had been threatening it since January. (Washington offered to make Johnson the sole commissioner, to no avail.) Thornton sensed an opportunity and spent most of July 1794 in Georgetown. He arrived just after the Commissioners sacked Hallet and just after Washington accepted Johnson's and Stuart's resignation. Washington made replacing Johnson a priority. Johnson, a former governor of Maryland and former chief judge of that state and former Justice of the Supreme Court, advised Washington to appoint a good lawyer to the Board.

Washington asked two Maryland lawyers,

a former governor and a former senator, but they declined. Then he

asked his Georgetown contacts about Gustavus Scott, a Virginia born Maryland lawyer who had held minor offices and had done more than most

in promoting the Potomac canal projects.

Ferdinando Fairfax then addressed Thornton's qualifications:

From a pretty good acquaintance with him, as well as from general repute, I believe him to possess uncommon Talents, and to have cultivated particularly those Branches of Science which are most useful in this business—and, what is of equal or perhaps more consequence, to have a large share of Public Spirit, and great integrity. He has a Plan of a National University, which appears to deserve attention, and w’ch, at some convenient time, he is desirous of submitting to your Consideration.There was no mention of the Capitol. Thornton had befriended Samuel Blodget who had initially won Washington's esteem with the same line about a National University.

Washington appointed Scott and then in late August offered the other vacancy to his former secretary Tobias Lear who was setting up a new merchant house on Rock Creek. Accustomed to men declining appointment, he also asked Lear about Thornton: “The Doctr is sensible, and indefatigable I am told, in the execution of whatever he engages; To which may be added his taste for architecture; but being little known, doubts arise on that head.”

There was no mention of the Capitol or

Hallet. Note that he did not say that Thornton was an architect. Lear declined appointment and replied:

I find Dr Thornton is much esteemed by those of the proprietors and others hereabouts from whom I have been in the way of drawing an opinion; they consider him as a very sensible, genteel and well informed Man, ardent in his pursuits; but liable to strong prejudices, and such I understand is his prejudice against Hoben that I conceive it would hardly be possible for them to agree on any points where each might consider himself as a judge—Weight of Character, from not being known, seems also to be wanting.

Lear probably thought he had ended

Thornton's chances by bringing up his feuding with James Hoban, the

architect at the President's house whose work there had never given

the President or Commissioners few problems. So Lear mentioned three

others that Washington might pick but in September, the new secretary of

state Edmund Randolph called on Thornton who was back in Philadelphia and offered him

the job. Although there is no evidence that they met at all that

summer, in coming years and after several battles with other architects over the Capitol design, Thornton would claim that Washington told him to restore the original design of the Capitol.

Thornton left Philadelphia and bought and moved into a house in Georgetown in October. Washington had just bought lots on a hill in the city just southeast of Georgetown and planned to build his city residence there. Thornton bought lots in the neighboring square. Scott commuted from a farm he owned nine miles from the city in Virginia and also began buying up city lots.

But a few months on the job, Thornton seemed to show that he understood Washington's wishes. He personally took the level of the ground around the Capitol. That drew attention to what many thought was Washington's obvious mistake in having L'Enfant place the Capitol too far to the west on Capitol Hill. Since 1791 when L'Enfant showed his plan, Washington had resisted moving it back. Then after crews of Irishmen, most speaking only Gaelic, dug the foundation, and masons, mostly Scots, laid the foundation as hired slaves moved stone to the site, the Capitol hardly seemed to rise because of the ground hulking behind it. Hallet had recognized the problem and had estimated how much it would cost to remove the hill.

The old Board assumed that brick-makers needing clay would level the hill in due time. While the building's foundation was stone, its walls would be brick fronted with sandstone. Thornton went to Philadelphia in March 1795 to do the paper work to get a bank loan to finance construction of the public buildings. Since he periodically had money from his legacy transferred from London, he knew Philadelphia bankers. (He didn't manage to raise a loan but it wasn't his fault.)

While in Philadelphia, he suggested to Washington that the foundation be raised ten feet. Thornton told his colleagues what he was up to and added, by the way, that both he and the President agreed that the Capitol was a building for the ages and it would not do to spare expense. Washington put off any decision until he viewed the site. One can credit Washington's eventual decision to raise the foundation walls six feet as an endorsement of Thornton's vision, although Washington probably felt compelled to rectify the mistake he made when he placed the Capitol too far to the west.

Washington was likely gratified that Thornton seemed to have thoroughly investigated the situation which is exactly what he wanted the new commissioners to do.

Then Thornton and Scott started a row with Thomas Johnson, the man Scott succeeded. Johnson had long worked with Washington to develop the Potomac Valley. When he first mentioned retiring, Johnson wrote to his old friend that he thought it was time "benefit myself by the rise of the City." He bought lots from James Greenleaf along Rock Creek just north of the stone bridge at K Street NW. When Johnson tried to get the deeds for the lots, the two new members of the Board told him that the old Board had not been authorized to award what were in effect water lots to Greenleaf.

Thornton enraged Johnson. So he who had used the “ideas of Thornton” in order to fire Hallet, took aim at Thornton. Alluding to his head bumping design of the Capitol's interior Johnson jibed in a letter that Thornton had a “head to clear of the lumber which crowds it to make room for what is correct.” Thornton and Scott sent a packet of documents and Johnson's offensive letters to the President. (See footnote 3.)

Washington tried to mediate the dispute and found both Johnson and Thornton stubborn. In a letter to Commissioner Carroll, he described his conversation with Thornton:

He, any more than Mr Johnson, seemed to think this could not be accomplished, as the Commissioners (or whether he confined it more particularly to Mr Scott and himself, I am not certain) were clearly of opinion, and had been so advised by professional men, that the lots upon Rock Creek would, undoubtedly, be considered as water lots under Greenleafs contract; and being so considered and of greater value, it followed as a consequence, that they, as trustees of public property in the City, could not yield to a claim which would establish a principle injurious to that property. He added that they had taken pains to investigate this right, and was possessed of a statement thereof which he or they (I am not sure which) wished me to look at. [(According to Tobias Lear, no one in Georgetown thought they were water lots.]Learning that Carroll was about to retire, Johnson warned the President that his choice for replacing Carroll was crucial. The other former Commissioner, David Stuart, told Washington that the two new Commissioners were "in error" and he had to appoint "a Law character of consderable eminence." He suggested Alexander White and Washington picked the 57 year old former two term Virginia congressman who had a farm in Woodville near Leesburg.

In explaining to White what he expected of him as a Commissioner, Washington shared his disappointment with Thornton and Scott:

In short, the only difference I could perceive between the proceedings of the old, and the new commissionrs result⟨ed⟩ from the following comparison. The old met not oftener than once a month, except on particular occasions; the new meet once or twice a week. In the interval, the old resided at their houses in the country; the new reside at their houses in George Town. The old... were obliged ⟨to⟩ trust to overseers, and superintendants to look to the execution; the new have gone more into the execution of it by contracts, and piece work, but rely equally, I fear, on others to see to the performance. These changes (tho’ for the better) by no means apply a radical cure to the evils that were complained of, nor will they justify the difference of compensation....Then on June – before White joined the Board, all of that year's work to date which entailed raising 300 feet of foundation walls for all three parts of the building, all fell down. Work resumed only on the North Wing. Both houses of congress would have to meet there in 1800. Washington did not lecture Thornton and Scott. He left that to Secretary of State Randolph who put it this way: "The President will by no means suppose, nor does he mean in the most distant manner to insinuate, that due attention was not paid by the Commissioners to the running up of the walls of the Capitol, but it may happen in some other instance that a similar fatality might take place which would be prevented by the watchful inspection of the Commissioners...."

Thornton and Scott wrote to Randolph complaining of the “motley set” they had to deal with which made inspecting the work distressing. They insisted that if they had walked on top of the faulty walls three time a day, they couldn't have prevented their collapse

Despite the strain the collapse of the walls caused between the Commissioners and President, everyone conspired to minimize reports of the damage. The Commissioners conducted an investigation only to assign blame so that the culprit would pay damages. So for years they carried on their account book that contractor Cornelius McDermott Roe owed $1264 for damages to the North Wing and $1470 for damages to the South Wing. On April 22, 1795, Roe had written to the Commissioners asking for the architect to give directions. Evidently he didn't receive an answer. No one investigated the Board's role in the collapse.

Then to save the Capitol from further blunders, upon the recommendation of the American artist John Trumbull, George Hadfield arrived from England having just graduated from the best architectural training in England and with the highest recommendations. The Commissioners hired him to do what Hallet had found impossible to do, build the plan which in one letter Washington would refer to as “nobody's.”

After being on the job but a few months Hadfield complained both about the design handed to him and the defective work already done on the building. He recommended not building the basement, which is to say, a story above the foundation and below the story with the Senate chamber. To add height to the building, he recommended building an attic. Thornton found an ally in James Hoban whose Irish friends working at the Capitol took an instant disliking to Hadfield. In a 2200 word letter to Washington, Thornton referred to Hoban 11 times including this fillip: “Mr Hoban we know to be a practical man, and a person on whom I think we may depend. He has sometimes opposed my wishes, but I knew his motives were good, and I always admire independence.”

To excuse defective workmanship, Thornton relied on Hoban's judgment: “Mr Hoban and I knew of these defects, not only in the foundation but also in some parts of the distribution of the interior—we lamented, and endeavoured to correct them—In some Instances we succeeded, some small ones may yet remain, but not of much Importance in our Estimation.”

As for Hadfield's criticisms of the building's design, Thornton was gracious to a point: Hadfield was “a young man of genius,” but incompetent. Thornton especially focused on one criticism made by Hadfield:

No objection can be urged to a rusticated Basement, because such are made use of not only in some of the most beautiful remains of Antiquity but also in the most magnificent modern Houses in England & other places—I will only instance a few in England. Wentworth House, which is an elegant palace belonging to the Marquis of Rockingham, six hundred feet in length—and of the same Order viz. the Corithian with a rustic Basement—Worksop-Manor House belonging to the Duke of Norfolk, three Hundred feet in extent yet only a small part of a superb Building once contemplated—Same Order rustic Basement. Holkham House—345 feet—Heveningham Hall, which is a very elegant Structure has a line of Pilasters supported on a rustic Arcade that runs the whole length—Chiswick House, the Seat of the Duke of Devonshire has a rustic Basement supporting fluted Columns of the Corinthian Order—Wentworth Castle, Seat of the Earl of Strafford abt 6 miles from Wentworth House is of the same Order on a rustic Arcade. Wanstead House is also Corinthian on a rustic Basement, & considered as a very chaste & beautiful Building—It was designed by the Author of the Book on Architecture called the Vitruvius Britannicus—These may serve to shew that a Basement (rusticated) is not only proper, but adopted by many of the first Architects. The expense is certainly less than any other mode of obtaining the same height.

Wanstead House, built in 1722, was the last of six private houses in England with basements that Thornton brought to the attention of George Washington. It was demolished in 1825 just before the original US Capitol was finished

Washington's reaction to that Vesuvius of Basements was muted. He wrote to Thornton on November 9, 1795: “If [Hadfield] is the man of science he is represented to be, and merits the character he brings; if his proposed alterations can be accomplished without enhancing the expence or involving delay; if he will oblige himself to carry on the building to its final completion; and if he has exhibited any specimens of being a man of industry and arrangement I should have no hesitation in giving it as my opinion that his plan ought to be adopted....”

In a letter to the Commissioners written the same day, he said he was busy with the upcoming session of congress. As for Hadfield's suggested changes “I should have no objection as he conceives his character as an Architect is in some measure at stake – and inasmuch as the present plan is no body's, but a compound of every body's....” He left the decision on the basement up to the Commissioners. However, on his last visit to the city, he was told that the dome had been eliminated from the plan which he did not like at all. Indeed, Thornton penned a new design with a huge cupola thrust high by columns letting light into all the rooms below. Washington did get the dome back, although he didn't live to see it built.

As long as he was a Commissioner, at least through 1800, Thornton worked on the designs of the Capitol at his own behest. This may have been one that shocked Washington into fearing that a dome was no longer part of the design

Ten years later President Thomas Jefferson would enjoy collaborating with Benjamin Latrobe as he designed and built the South Wing of the Capitol. Washington did not want to collaborate with Thornton at all. He wanted Hadfield to supervise construction of the Capitol to its completion. And he wanted the Commissioners to be on the scene making sure that the work progressed. Washington made it clear in a June 6, 1796, letter to the Board's treasurer William Deakins that the Commissioners must live in the city, that living in Georgetown wasn't enough. But not until December 1796, did Thornton arrange to move into the rental at 1331 F Street NW that became his home for the rest of his life. Washington congratulated him for choosing such a central location. (Not until February 1798, almost a year after Washington left office, did Mrs. Thornton host her first tea there.)

Washington's gratitude was probably genuine because Thornton's colleagues never moved to the city. Scott had bought a small house just over the city's boundary and expanded Rock Hill into a house suitable for his family of nine. White didn't move to the city because after a stay of a few weeks, his wife refused to live there. Anyway, his main contribution was lobbying congress for loan guarantees which kept him Philadelphia for months when congress was in session. That also kept him near the president who found the former congressman reliable and trustworthy.

But Thornton's tardy move must have puzzled Washington because Thornton had money and just after Washington bought lots in 1794, Thornton bought lots nearby. That created the expectation that Thornton would make a major commitment to the city. In 1794 Washington expected to make a major sale of his Westernlands but when the land deal failed (it was probably with Greenleaf and Morris,) Washington forgot about building. So did Thornton, but he still had money to spend on housing. Just as he did in Philadelphia when he gave up his short lived medical practice (just in time to miss the deadly 1793 yellow fever epidemic,) he bought a farm just outside the District of Columbia. It was not too much farther from his house in Georgetown to his farm, then it was to the Capitol. He also bought city lots cheaply when proprietors put up their less desirable lots for auction.

One of the squares in which he bought lots in May 1797 was across the street from the lot Tayloe bought in April. Likely Thornton had an eye on the long projected development around the planned Mall to the east of his lot where foreign governments would be required to build their embassies. Thornton also noticed the emergence of mud flats in the Potomac south of the President's house, and beginning in September 5, 1795, obtained warrants to register a claim to them.

John Nicholson mistook Thornton for a player in the high stakes game of speculating on the ups and mostly downs of Morris's and Nicholson's vast holdings in the city and elsewhere. Perhaps Thornton's kindness in sharing a “good pipe of Madeira,” gave the speculator the wrong idea. He wrote to Morris on December 9, 1796, that he “made a strong attack on him to get his paper to settle with Gen. Bailey but he parried, said his wife and mother-in-law would be alarmed.” Nicholson needed “paper” to fulfill a contract that Greenleaf had made to buy land from Bailey.

The failure of Greenleaf, Morris and Nicholson to fulfill their contract to buy 6000 public lots prompted Washington and the Commissioners to frown on sales of lots to speculators. The Commissioners wanted buyers to build houses and soon. So they began offering two prices to all buyers giving a discount of 20% to 30% to those who built a brick house on a lot within three years. (NB: that clock did not tick on the lots Washington and Thornton had bought before the new rule.) That policy did not sit well with many buyers given that original proprietors and those to whom they sold lots had no building requirement.

Washington's plan for two "plain" houses

In September 1798, a year and a half after retiring from office, Washington decided to buy two more lots in the city and set a pattern for other gentlemen to follow. He immediately put in motion his plan to build two houses suitable for renting to those coming to the city in 1800. Well knowing the complications involved in buying lots and building in the city, he sought the help of Commissioners. He didn't want to involve the full board until he picked his lots so he decided to first ask one of them for help. He could choose Thornton the architect, Scott who Deakins had told him was the best at making contracts, or Alexander White. He seemed the least qualified Commissioner to lend a hand. He hadn't bought any Washington lots for building or speculation.

Washington asked White to pick out two lots near the Capitol that would be a good site for two “plain” houses. He also sent White a design of the houses that he said he had made himself and asked White to get the Commissioners to make a contract with a suitable builder. Washington knew that Thornton would soon learn of his intentions and made a comment to White in a way that must have given White a chuckle: “My plan when it comes to be examined, may be radically wrong; if so, I persuade myself that Doctr Thornton (who understands these matters well) will have the goodness to suggest alterations.”

White's last exposure to Thornton's "goodness" on architectural principles came earlier in 1798. Thornton discovered a mistake Hadfield made in the size and placement of a cornice which resulted in a rose carved in a medallion that was an inch and three quarters too small and thus "not in proportion recommended by Sir Wm. Chambers in his work on architecture which is admitted to be a work inestimable in its way." Thornton's colleagues refused to spend $1100 to make it right. Thornton protested that the cornices "will remain forever a laughing stock to architects."

Thornton took pride in his battles with architects. In an October 5, 1797, letter to a mentor in Britain he recalled his early experiences defending his design of the Capitol: “I was attacked by Italian, French and English – I came off, however victorious. President Washington's determination joined by the Commissioners, after long and patient attention to all, was final and in my favor.” (The Italian he referred to was probably a model maker named Provini who worked with Hallet..)

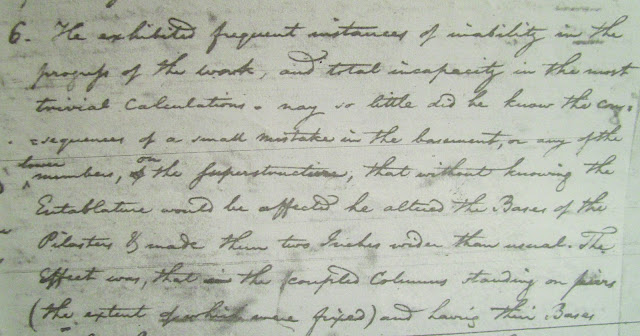

He soon had another victory. As he continued his 1798 attack on Hadfield, Thornton again found an ally in Hoban. With work on the President's house put on hold to get the Capitol ready, Hoban wanted to become superintending architect at the Capitol. In a March 27, 1798, letter to his colleagues demeaning Hadfield, Thornton relied mostly on retelling what Irish carpenters closely allied to Hoban characterized as Hadfield's inept attempt to supervise construction of the Capitol's roof. Thornton recalled Hadfield's mistakes in arithmetic, his “total incapacity in the most trivial calculations,” and deficiencies mere Irish carpenters would not notice. Hadfield operated “as if the 47 proofs of the first book of Euclid had never been discovered.” After a good bit of back and forth, the Commissioners fired Hadfield at the end of May.

"nay so little did he know of the consequences of a small mistake in the basement..."

Thornton takes Hadfield to task in a letter to his fellow Commissioners

A few months later Washington wanted to build two “plain” houses. He did not ask Thornton to design them, likely.to avoid his histrionics. But as he avoided Thornton the architect, he had to avoid provoking Thornton the architecture critic. Could Thornton ever criticize the man who made him famous? Washington had to remember Thornton's unwarranted attacks on his old friend Thomas Johnson.

On September 21,1798, the Commissioners finalized Washington's lot selection as the former President joined them on Capitol Hill. They sent the house plans to George Blagden who had been the head mason at the Capitol and with that work ending had become a private builder. There is absolutely no evidence that Thornton had anything to do with the plan they gave to Blagden who then estimated how much it would cost to build. But that same day, Thornton sensed an opportunity to get more involved in the project.

Since 1793 he had never claimed the lot that along with $500 was the prize for winning the Capitol design contest. So on the day Washington chose his lots, Thornton asked his colleagues that he be awarded a lot. He justified bringing it up at that late date by noting that he had finally restored the design of the Capitol. His colleagues took him at his word. They arranged for him to choose a lot and he took one next to Washington's. Thornton also joined White in drawing up a contract with Blagden and listing the specifications for the houses. (When he mentioned getting his prize lot in a letter to Washington, he only said of the prize lot that until then he “had not demanded [it] from motives of Delicacy....” He didn't push the idea that he had “restored” the Capitol design.)

Then, Thornton volunteered to help Washington save money by building a three story brick house “or Houses on a similar plan” next door and assuming the full cost of the party wall. That is, he would build as soon as he recovered from “some late heavy losses; not in Speculations, but matters of Confidence, to the amount of between four and five thousand Dollars.”

Washington replied on October 28th just as he met with the contractor Blagden to go over the specifications of the house. He welcomed Thornton's offer without “any allowance being made... as the kindnesses I have received from you greatly overpay any little convenience or benefit you can derive from my Wall.” (The best documented “kindness” that Thornton gave to Washington was a gift of special medicinal "Tincture of bark" made at his Virgin Islands plantation.)

Could the design for Washington's house have been another kindness from Thornton? No. Washington wrote: “With respect to your own accomodation you will please to give Mr Blagden such Instructions when he enters upon the Walls as to suit your views perfectly.” If Thornton had designed Washington's house, he would have already known how Blagden would build the wall. We could say Thornton designed the party wall, but he never built his house.

In that same letter Washington asked Thornton to oblige with another kindness: “as you reside in the City, and [are] always there, and have moreover been so obliging as to offer to receive the Bills and pay their amount (when presented by Mr Blagden) I will avail myself of this kindness.” As Mrs.Thornton proudly noted when she viewed the almost completed Washington houses on January 3, 1800: “the money paid to the undertaker of them having all gone thro' my husband's hand, he having Superintended them as a friend.” She didn't add that her husband designed the houses because he didn't.

He did try to do more than merely pay off the

contractor. He gave Washington advice on parapets, which Washington

didn't take, and replaced wooden sills with stone at some outer

doors. Then in July 1799 once again Thornton brought up expanding

Washington's two houses into a row of houses.

John Francis who boarded congressmen in Philadelphia

had immediately expressed an interest in renting Washington's houses.

Washington asked Thornton what the customary rent would be. Thornton

researched the issue and suggested a rent of 10% of the cost of

construction which would have been $1200 for both houses. Francis

also approached Commissioner Thornton to see if he could buy a lot

and build next to Washington. He needed more room for

boarders. Since Francis also wanted to build back buildings behind

Washington's houses, Thornton “refused to name any price,” and Francs lost interest. But not to

worry, if Francis hesitated to rent Washington's houses, Thornton had a better idea:

...preserve them unrented, and keep them for sale, fixing a price on them together or separately; and I have no Doubt you could sell them for nine or ten thousand Dollars each, and if you were inclined to lay out the proceeds again in building other Houses this might be repeated to your Advantage, without any trouble, with perfect safety from risk, and to the great improvement of the City. I am induced to think the Houses would sell very well, because their Situation is uncommonly fine, and the Exterior of the Houses is calculated to attract notice. Many Gentlemen of Fortune will visit the City and be suddenly inclined to fix here. They will find your Houses perfectly suitable, being not only commodious but elegant.Thornton added “You have done all in your power to render them convenient for a lodging-house without absolutely injuring the Tenements...” In reply, other than thanking him "for the information, and sentiments," Washington didn't react to Thornton's suggestion that in the waning years of his illustrious career he become a real estate developer.

That Thornton didn't design Washington's houses doesn't prove that he didn't design the Octagon. Indeed snubbed by Washington, why wouldn't Thornton be chomping at the bit to design someone else's house? Don't cringe at the metaphor. Not until Glenn Brown's 1888 article in American Architect and Builder News were Thornton and Tayloe paired in regards to the Octagon. Throughout the 19th century, there names were both mentioned in articles and books about racing and breeding horses.

It is easy to picture young Tayloe, only 29 in 1799, asking the famous architect, then 42, for a house design. Tayloe split his time between his plantation near Richmond and his wife's family home in Annapolis and only passed through Georgetown. He had little time to meet other architects or hear about the problematic side of Thornton.

Blurring that picture is that in 1799, young Tayloe's horses dominated American horse racing. In that regard, Thornton was simply not in his league. As for architecture, while Thornton had seen the great houses of Britain at least in picture books, young Tayloe likely had been inside some hobnobbing with their owners. Tayloe had attended Eton and Cambridge. His son Benjamin later wrote that his father had been "on terms of great intimacy with the Marquis of Waterford, the Beresfords, Lord Graves and Sir Grey Skipwith a native of Virginia, through whom he had access to the best society in England...."

Tayloe's school chum Grey Skipwith would inherit Newbold Revel from a relative in Warwickshire

So Tayloe was not unfamiliar with English houses.Tayloe's best friend at college, Edward Thornton, was humbly born but became a leading British diplomat and courtier. Edward Thornton was serving in the US while the Octagon was being built. Tayloe did not necessarily learn about parapets from William Thornton.

We cannot be sure when Tayloe and Thornton became friends. Given that a horse race in early Washington would always be an occasion for socializing, it likely that Thornton and Tayloe met at least by April 1797.when Tayloe's horse won a match race with Charles Ridgely's. (Hampton, Ridgely's estate just north of Baltimore, rivaled Tayloe's Mount Airy just north of Richmond.) Tayloe bought the lot upon which the Octagon would be built in April 1797. As I point out in Part Two of this essay, there is no evidence that he thought about what to build on the lot until February 1799 when George Washington advised him to run for congress rather than accept appointment as an officer in the army. If elected, he would need a house in Washington. (He lost by a wide margin but still made the Octagon his winter residence for the rest of his life.)

Between April 1797 and April 1799, there is no evident that Tayloe, who was rarely in Washingon, had much to do with Thornton, who rarely left it. In the fall of 797 the Thorntons toured Virginia going to Monticello and Montpelier but not Mount Airy.

After that, what evidence we have suggests that Tayloe and Thornton continued to have a distant relationship.In October 1798 Washington asked Thornton about land purchases made by Henry Lee. Thornton thought that Lee might have sold some lots to "J. Tayloe of Mount Airy" but he would have to see those gentlemen to be sure. Thornton mentioned "J. Tayloe of Virga" in his April 19, 1799, letter to Washington reporting that Tayloe made a contract for his house. (The formal way of identifying Tayloe suggests that Thornton didn't realize that Tayloe and Washington were rather close. He spent the night of April 17 at Mount Vernon. On March 31 Washington had written to Tayloe that “at all times and upon all occasions I should be glad to see you under my roof.")

The earliest indication that Thornton and Tayloe were friends is in another letter to Washington in which Thornton reported that he did not go to Mount Vernon as planned because he and his wife "spent the day" with "John Tayloe of Mount Airy." That day was August 31, 1799, well after the Octagon was designed. Perhaps they spent the day viewing the Octagon, but then as now, one usually spent a day with someone in the countryside not in the city taking care of business. In 1799 Thornton imported a notable horse; Tayloe imported several.

Of course, Thornton could design a house anytime or anywhere he wanted. In the Thornton papers at the Library of Congress there are two unsigned floor plans that curators and scholars consider preliminary plans for the Octagon. The drawings only resemble what was built so Orlando Ridout V in Building the Octagon assumed that what would have been Thornton's third plan was what William Lovering followed when he served as the project's superintending architect.

If those two extant plans were indeed made for Octagon by Thornton, then Thornton showed not a little brass. Shortly after those floor plans had to have been made if they were for the Octagon, a battle between Thornton and Hoban came to a head. Three years later in a July 13, 1802 letter to President Jefferson, Alexander White recalled the episode: “Some years ago both my Colleagues were desirous of getting Hoban out of the way; and amazing exertions were made to find something in his conduct which would justify them in dismissing him.”

Thornton did not emerge unscathed. In an April 12, 1799, letter to White, Hoban's head carpenter Redmond Purcell felt "determined to pour broadsides" into the hulls of Thornton and Scott. Purcell accused "the fribbling quack architect" of signing "his name to the only drawings of sections for the Capitol ever delivered to the commissioners' office, made out by another man." The letter was soon published.

Hoban's counterattack was more effective. If the Commissioners attacked him for not doing his job, he would attack the so-called architect for not doing his. In a March 12, 1799, letter, he told the Commissioners of the difficulties he had answering their request for a breakdown of future costs at the Capitol. He had no "plan or sections of the building to calculate by, not the parts in detail, all which should be put into the hands of the superintendent." Investigations of his past handling of workers at the President's house continued. So on April 15, he pointedly asked for "drawings necessary to carry on the work on the staircases and the Senate and House chambers.'

Hoban asked for drawings that he knew that Thornton could not provide

Commissioner White forced Commissioner Scott, who also wanted Hoban out, to change sides. In the invitation for the design contest, there was a requirement that the winning architect provide drawings needed during construction of the building. His colleagues asked Thornton to provide the drawings. He didn't, likely because even though he boasted of restoring his design of the Capitol, he couldn't provide the drawings needed to build it. He told his colleagues, rightly, that Hadfield had been hired to do that. Of course, when Hadfield made drawings, Thornton ridiculed them.

But while taking that stand, how could Thornton at the same time provide a detailed design for the Octagon house? Judging from what Lovering wrote to the Commissioners in October, 1798, it was common knowledge that Thornton was "unacquainted with the trouble of architectural details." Lovering discussed a contract for building the Octagon on or shortly before March 9, 1799. He likely would have learned if the house plans with enough detail to allow a cost estimate had been made by Thornton. It is unlikely Thornton could have gotten away with secretly designing the Octagon.

The floor plan in Thornton's paper which is less like the actual Octagon is likely a design that Mrs. Thornton described her husband making on February 1 and 2, 1800, for a house he told his wife that they would build on the square below the square where Tayloe was building his house. Tayloe built on the corner of New York Avenue and 18th Street, north of the avenue and east of the street. Thornton planned his house for his lots on New York Avenue and 17th Street, south of the avenue and west of 17th Street. Both houses had to fit in a lot shaped by the angle of New York Avenue to 17th and 18th Streets.

The central axis of the house is quite like Thornton's floor plan for the middle the Capitol.

If Thornton had offered that house design so reminiscent of his design for the yet unbuilt rotunda of the Capitol, Tayloe did not go for it. The Octagon as built is different.

Is it likely that after defending his Capitol design with increasing vehemence since 1793, Thornton would radically alter his first take on the Octagon and eliminate the line up of ovals reminiscent of his Capitol design? The other design in Thornton's papers is more like what was built.

But could he have exhausted himself with such detail?

There is another explanation for how a design so similar to the Octagon wound up in Thornton's papers. In describing how he designed the Library Company building and the Capitol, Thornton almost boasted that he consulted books implying that using them substituted for being trained in architecture. So prior to designing his own house, he likely asked Lovering for one of his preliminary designs for the Octagon.

Lovering had chided the Commissioners in 1798, but in 1799 they still asked him to inspect the roofs of the President's house and Capitol. As noted in Part Two of this essay, we know from Henri Stier's letters that Lovering liked to give prospective patrons three designs. Perhaps Thornton's request so impressed Lovering that in May when he advertised his move to Georgetown, he offered specimens of his designs for houses built on angled avenues which probably also included a house he designed and built for Thomas Law on New Jersey Avenue.

That the houses Lovering in 1794 and 1795 for Greenleaf, and the Twenty Buildings he designed for Morris and Nicholson don't have the ovals or look of the Octagon shouldn't be held against him. After doing those houses, he measured work done at the President house and Capitol to determine the compensation for workers. He was by no means unfamiliar with the ovals of those buildings. The angle of the streets dictated the need for a novel design and ovals discretely used (not lined up a la Thornton) was the obvious solution.

Assuming that Lovering made the preliminary drawing of the Octagon found in Thornton's papers, frees Thornton from an accusation that he worked on details of Octagon at the same time he refused to make detailed drawings for the Capitol.

This is not to say that Tayloe avoided involving Thornton in the project. He seems to have known that Tayloe ordered chimney pieces from London. When chimney they came in November 1800, Thornton went to see them. Judging from Mrs. Thornton's diary it was the only time in 1800 that Thornton went inside the house.

Thornton did design houses, but only after work began on the Octagon. By not asking him to design his house, Washington shocked Thornton into making his talents as a designer more serviceable. So in 1800 while he remained busy as a Commissioner, Thornton began his modest career as a house designer. A double house for Daniel Carroll was easy given the experience he had helping to draw up the contract for Washington's two houses. His obsession in 1800 was a monument, if not a mausoleum, for George Washington. So he maintained close ties to the Washington family. He found that easiest to do by befriending two grand daughters of Martha Washington and their husbands Thomas Peter and Lawrence Lewis. Two of the most gracious acts of his life were gifting house designs to both couples.

Then why didn't Lovering become famous for designing the Octagon? That he was not a gentleman and already famous are two reasons. Also in June 1801, after two years of work, the project was well over budget and far from being finished. Tayloe came on site and urged Lovering to get it done. At a time when an architect was also expected to build what he designed, his failure as a builder could eclipse the credit he might deserve for being the designer. The pity of continuing to celebrate Thornton as the Octagon's architect is that we lose sight of the problems faced by the handful of men who had the talent to design and build. None of them were born rich like Thornton or became rich off their work. Don't we owe them something?

Bob Arnebeck